How the police and academia are discovering each other in Switzerland

Jonas Hagmann, Anna Wolf

10th January 2024

Swiss police work is strongly geared to practical knowledge, yet collaborations with academia are finally becoming more frequent. A new monitoring of scientific publications tracks the contours of this emergent subfield of Swiss police research. What academic disciplines contribute to it, and what research methods and types of quality control are employed? First results point to a surprisingly modest presence of social science research focussing on police in Switzerland.

Introduction

The police is undoubtedly one of the most powerful means of social steering at disposal to the Swiss executive branch.1 The police provides security and public order through an array of preventive and repressive means, and it consumes significant amounts of public funding. It enforces norms also against the will of individuals, works at the intersection of innumerable social problems, and represents the desired Swiss balance between public and private forms of social ordering. With its on-site decision powers, the police is also qualified the very essence of ‘the political’ by some scholars.

Considering this central position, it is little surprising that the police is recurrently subject to public debates at cantonal levels. Alas, policing is still poorly researched in Switzerland, and not much publically available documentation about Swiss police work exists today. In many respects, this reflects the practice-oriented nature of the field. The Swiss police domain consists of a sizable practitioner community comprising about 19’500 police officers, professionals whose ways of working is largely grounded in practices that are trained and passed on from one officer to another. Legal opinions, internal regulations and teaching materials aside, there exist only few written and scholarly texts about Swiss policing.

A proven need for translational knowledge production

Indeed, different to cases like Germany, the UK or Canada, collaborations between the police and academia are still poorly developed in Switzerland today. There are few written accounts of police work, and new insights into the field are published at a slow pace only. Analytical work within the police is not consistently supported by proven research methods, and the benefits of scholarly work are not recognised by all cantonal police forces. At the same time, scholarship recurrently strikes as exceedingly externalist: More often than not, the field of domestic security is analysed from a formal legal perspective and “afar”, with little knowledge of the powerful practical logics inherent to the professional domain. At times, international debates about the politics of policing are imposed on the Swiss field of policing, with no test of the appropriateness of such application to that distinctive context.

Research with and about the police is no particularly systematic practice in Switzerland today, and mutually beneficial collaborations still depend fairly strongly on personal relations. This is no satisfactory situation for the social and political sciences in particular, given the police’s central governmental role and social ordering functions. It is also unsatisfactory for the police itself, however. Police forces must handle increasingly complex mandates, and they face important staff shortages. As such, they must gain much better access to state-of-the-art research, and they must leverage scientific insights in support of their tasks. There is a strong need to collaborative learning, and demands for evidence-based policing are growing rapidly. The latter approach requires a stronger emphasis on objective data, and it necessitates more numerous traceable analytical products that are written and methodologically robust. Taking things together, the Swiss police forces have – just like other, modern and democratic police systems – a strong need to strengthen themselves as knowledge-based organisations. There is an obvious need for closer collaboration with academia.

A new monitoring of scholarly work about the police

This rapprochement requires time, however, and a number of barriers exist on the path towards a more mutually beneficial type of knowledge co-production by police practitioners and academics. One challenge is to strengthen the social and political science components of contemporary police research. A first systematisation of publication practices shows that research about Swiss police is indeed fairly one-sided. Needless to say, scholarly publications are not the only measure of knowledge production in and about police. By making results accessible to wider publics and empowering cumulative research, publications are yet a highly practicable means for such a mapping (in political science see Leifeld and Ingold 2016). This is why the Division for Police Sciences of the Cantonal Police of Basel-Stadt has, since early 2022, been monitoring all scientific texts that are being published in German, French, Italian or English and focussing on Swiss police.2 The thus-created overviews are used internally, made public every six months, and analysed bibliometrically.

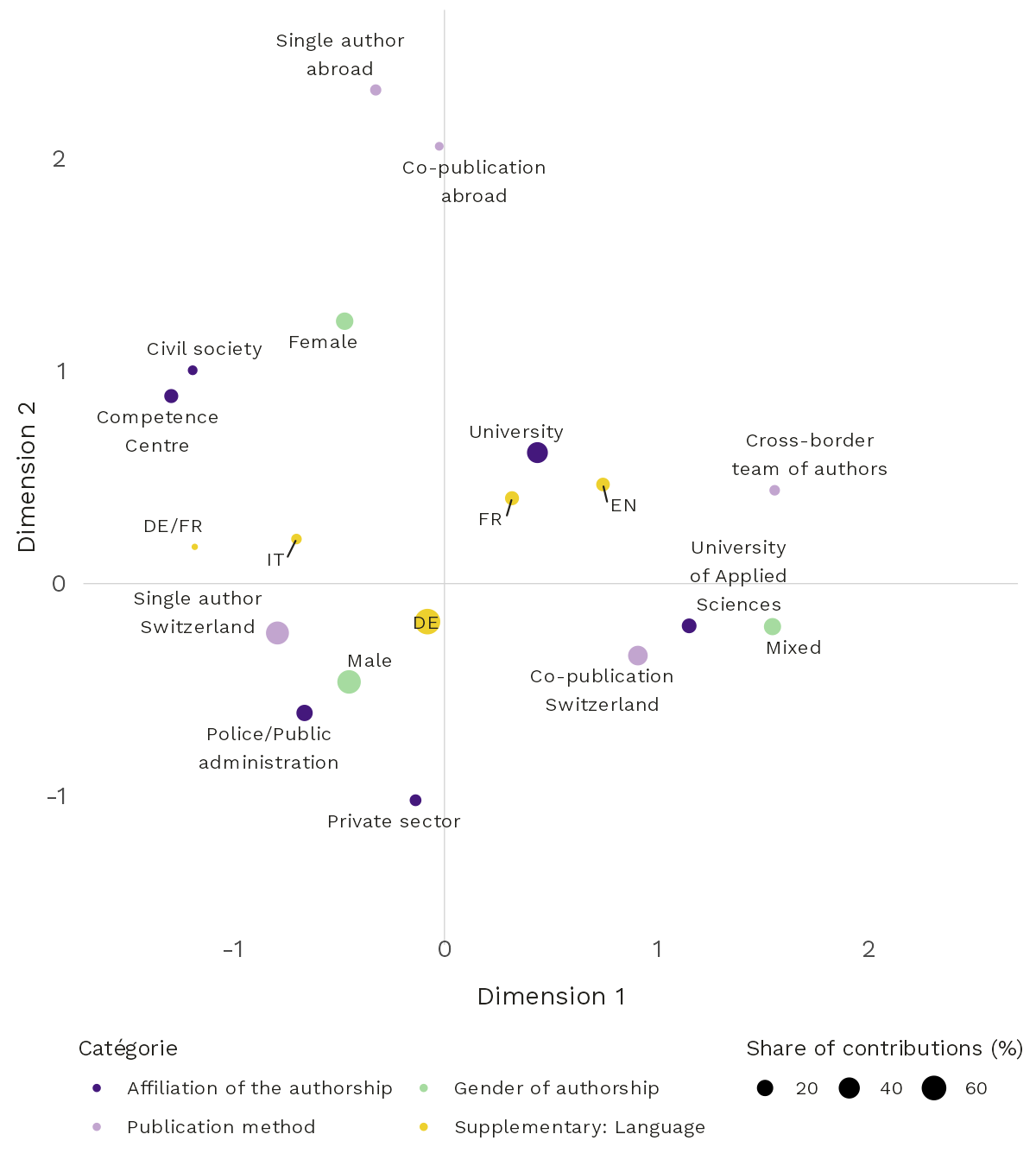

Illustration 1. Bibliometric structures of research focusing on Swiss police in the year 2022 (publication language projected)

Illustration: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto

The collection effort creates an increasingly rich dataset about police research, and it helps making its structures ever more visible.3 The first annual dataset already offers instructive insights: In the year 2022, exactly 101 scientific publications focused on Swiss police. Of these, 45% appeared in non-refereed magazines, 28% in further practitioner outlets, 16% in peer-reviewed journals, 11% as books and 1% as book chapters. 53% of the 101 texts were written by men, 24% by women and 23% by mixed author teams. 50% of the publications were composed by single authors, and 33% by co-authors from Switzerland, 7% by single authors and 4% by co-authors abroad, and 6% by transnational author teams comprising Swiss and non-Swiss authors. 66% were published in German, 13% in French, 12% in English and 6% in Italian, the remainder is bilingual.

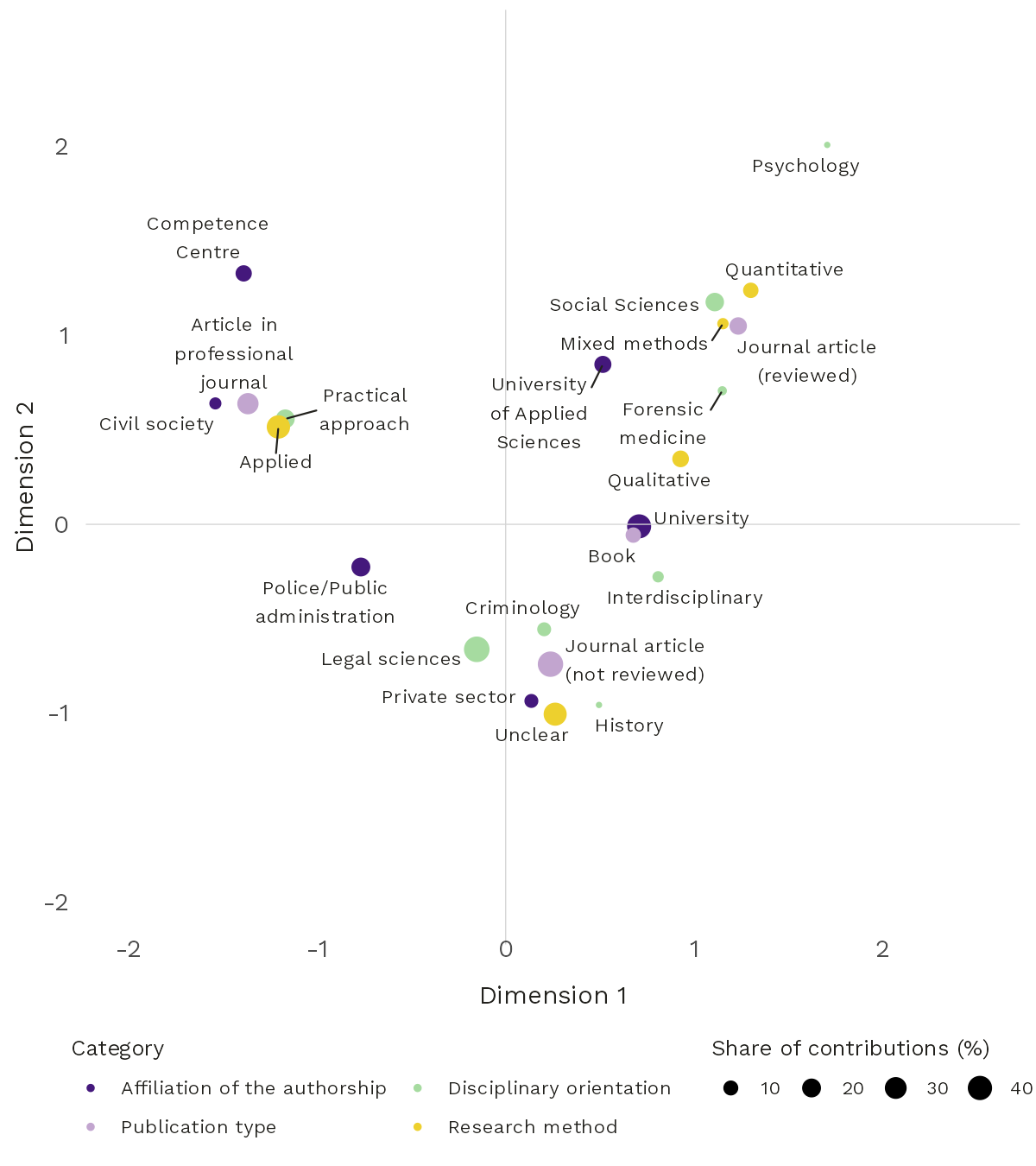

The police domain necessarily has to anchor its practices in detailed legal provisions, and this also shows itself in the disciplinary penchants of police research. With 46%, almost half of all scientific texts of the year 2022 come from legal studies, 20% are in applied police work, 8% in criminology, 2% in forensic medicine, and 1% each in psychology and history. A mere 19% of the works is at home in the social sciences, another 4% are interdisciplinary in nature. Similarly, only 14% of all works rely on qualitative and 11% on quantitative methods. All other texts are of an “applied nature” or do not use clearly discernible scientific research methods. As per author affiliations, 39% of the 101 contributions come from universities, 20% from police and public administration, 15% from universities of applied sciences, 8% from the private sector and 5% from civil society organisations.

The idiosyncrasies of published police research

With these results, the analysis reveals specific publications patterns: Single-authored publications by male authors correspond with texts written in German and from a practitioner perspective. Co-authored texts cluster with mixed author teams comprising male and female scholars, as well as writes based at universities of applied sciences. Texts written in English correspond with transnational author teams and universities (see illustration 1 for these clusters). Also, practitioners tend to publish either applied texts focusing on police practices, or legal and criminological analyses, in non-refereed outlets. Contributions by researchers working at universities – and at universities of applied sciences especially – are clearer in their choice of methods, and they correspond more closely with the social sciences and peer-reviewed texts (cf. illustration 2).

The coding also highlights knowledge production features that partly diverge from those observed in classic disciplines, such as political science. Swiss police research is – given its focus on a practitioner world anchored at the subnational cantonal scale – essentially published in national languages. This is different to research articles of political scientists in Switzerland, who write in English to contribute to the international state-of-the-art, and whose texts thus barely circulate within Swiss public administration (and even less so at the cantonal level). By contrast, transnational publications are less frequent in police research, the domain’s profound pan-European links notwithstanding. The gender ratios are similarly imbalanced in police research and political science alike (Leifeld and Ingold 2016, Teele and Thelen 2017, Cellini 2022). Little surprising, scholars from universities of applied sciences are better represented in police research than political science (Bernauer und Gilardi 2010). Police research is also less often peer-reviewed and its methods are more difficult to identify, a feature that makes it more difficult to verify its findings. Finally, there is a strong bias to legal studies in police research and the social sciences only make limited contributions to it.

Illustration 2. Disciplinary and methodological penchants in police research in the year 2022

Illustration: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto

Police and academia are supposed to collaborate more closely also in Switzerland. When the respective barriers are being reduced, do the bibliometric characteristics of police research change as well – and if so in what direction? The continuation of the publication monitoring will allow to interpret the results of the year 2022 with more confidence, and to better grasp and problematize the expected methodological and disciplinary developments of the field. With this, the monitoring is part of a larger ambition to accompany and improve the linkages between police and academia in Switzerland. Seen from today, the need for an increasingly professional and translational kind of research community in and around Swiss police strikes as evident (Jarchow and Kagel 2023). Such a research approach doesn’t pit epistemes against each other, but seeks to combine practical and scholarly knowledge in productive ways. It seeks to enhance the methodological robustness of police research, to empower better police research in general and to also promote social science research questions. Considering the profound social and political relevance of the police, it is overdue to subject the domain and its powerful (inter-)cantonal, communal and (trans-)national relations much more systematically to social science research.4 The intimate relations between police, politics, government, order and power are well known to any political scientist and deserve – if not require – considerably more thorough analysis.

1 This contribution contains the arguments and interpretations of its authors. It denotes no official position of the Cantonal Police of Basel-Stadt.

2 The Division for Police Sciences is a newly created hybrid research entity. The Division conducts research with, for and about police. It combines practitioner knowledge with the scholarly state-of-the-art and focuses thematically on current issues of urban policing.

3 It also connects to related analyses in international police studies. See Beckman et al. 2003 and Wu et al. 2018. The monitoring is available via website and newsletter on www.polizei.bs.ch/wissenschaft, as are other products of the Division for Police Sciences.

4 As per November 2023, only two articles with the term “police” in title or keywords have been published by the Swiss Political Science Review (since its creation in 1995), and a mere three such articles by the Swiss Journal for Sociology (since its establishment in 1976).

Bibliography:

- Beckman, Karen, Cynthia Lum, Laura Wyckoff und Kristine Larsen-Vander Wall (2003). Trends in police research: a cross-sectional analysis of the 2000 literature. Police Practice and Research 4(1): 79–96.

- Bernauer, Thomas und Fabrizio Gilardi (2010). Publication output of Swiss political science departments. Swiss Political Science Review 16(2): 279–303.

- Cellini, Marco (2022). Gender gap in political science: an analysis of the scientific publications and career paths of Italian political scientists. Political Science & Politics 55(1): 142–148.

- Jarchow, Esther und Martin Kagel (2023). Polizei vs. Forschung? Ein spezifisches Forum für Polizeiforschung als Missing Link und als Fallbeispiel für Wissenschaftskommunikation im polizeilichen Kontext. In: Kritische Polizeiforschung: Reflexionen, Dilemmata und Erfahrungen aus der Praxis. Maurer, Nadja, Annabelle Möhnle und Nils Zurawksi (eds.). Bielefeld: Transcript, pp.231–247.

- Leifeld, Philip und Karin Ingold (2016). Co-authorship networks in Swiss political research. Swiss Political Science Review 22(2): 264–287.

- Teele, Dawn und Kathleen Thelen (2017). Gender in the journals: publication patterns in political science. Political Science & Politics50(2): 433–447.

- Wu, Xiaoyun, Julie Grieco, Sean Wire, Alese Wooditch und Jordan Nicols (2018). Trends in police research: a cross-sectional analysis of the 2010–2014 literature. Police Practice and Research 19(6): 609–616.

This article was edited by Sarah Bütikofer and Remo Parisi.

Image: Midjourney / Hagmann 2023 (AI-generated image)