One of the most noticeable changes in European politics is the rise of green and radical right populist parties in the last three decades. The electoral success of these parties results from the increased salience of so-called cultural conflicts on issues such as new social values, minority rights, immigration, national sovereignty, or European integration. The political science literature subsumes these as being part of a new cultural cleavage, named transnational or globalization cleavage. Importantly, green and radical right populist parties are said to mobilize their voters based on these cultural issues; culturally progressive voters vote for green parties, culturally conservative parties vote for the populist right.

Since green parties – the ‘new left’ – often grow at the expense the ‘old left’, the rise of these parties has been perceived as a threat to a generous and encompassing welfare state, a core issue of the progressive agenda. According to this line of argument, the rise of green parties threatens the welfare state, either because green voters are not economically left, or because as a cultural force green parties do not care enough about a distributive issue such as the welfare state. Both arguments seem plausible at first view: Green voters tend to be from the educated middle class. In classical political economy accounts, both income and education tend to be related invertedly with support for the welfare state, an economically conservative position of green voters would therefore be rational. By catering to voters with higher levels of education and material wellbeing, progressive parties will dilute their progressive agenda to adapt to more market-liberal demands of progressive but better-off voters. Equally, it is plausible to assume that as a cultural force green parties do not care much about the welfare state but focus on so-called ‘cultural’ or ‘new value’ issues such as the environment, minority rights, or immigration. This research brief dismantles both arguments. Based on recent studies on the implications of the rise of green parties for distributive politics, we demonstrate that a) green voters are part of a pro-welfare state voter coalition and b) that green parties place considerable salience on the welfare state in their electoral programs. With this, the research brief challenges the idea that there is a dilemma between culturally and economically progressive positions.

The research brief is structured in two parts: The first part discusses research on the attitudes of green voters on the socio-economic dimension of political competition and the second part discusses evidence on green parties’ positions on the same dimensions.

Demand side of politics: The distributive preferences of green voters

Green parties rely on the educated middle class as their electoral backbone. Research from political sociology shows that the core voters of green parties is the “new” middle class (Kriesi, 1998; Dolezal 2010, Bremer and Schwander 2022). Green voters are younger and more likely to be female than other voters. They are also much more likely to have a higher educational background, work in the public sector, and live in an urban area than other voters. In short, they are the winners of the transition from an industrial to a post-industrial, knowledge-based service economy. They fill the new service (and often public-sector) jobs that demand specialized expertise and knowledge. Now, in contrast to the fear about the end of the welfare state as a result of the rise of green parties, this part of the middle class is pronouncedly welfare state friendly, as we will elaborate now (see Macarena Ares’ research brief “A progressive service-class coalition” on the welfare state attitudes and political orientation of the industrial and service classes).

The reason for the more nuanced relationship between socio-structural endowment and welfare state preferences lies in the structural transitions outlined in the introduction to this research brief series, namely the transition towards a post-industrial knowledge economy in the world’s advanced capitalist economies. By skewing the employment structure towards more skilled jobs in the service sector and making the work force more female, this transition led to an expansion of the middle class. By expanding, the middle class grew more heterogeneous, leading to an old middle class (the petty bourgeoisie, managers or the liberal professions) and a new middle class that typically works in (skilled) service-sector occupations as teachers, nurses, or journalists (Oesch 2006). The division not only bears relevance in terms of work conditions but also in terms of their political orientation. Because the professionals in these service-sector occupations are engaged in regular contact with their clients and patients, they are more likely to be responsive to social needs while they themselves enjoy a considerable amount of autonomy in their work (Kriesi 1998). This part of the middle class, therefore, favors egalitarian values and places a high emphasis on individual autonomy (Kitschelt 1994, Oesch 2006).

While this “left-libertarian” value orientation of the new middle class explains their affinity to vote for left-libertarian parties such as green parties, it also bears implications for their attitudes towards the welfare state. Their work environment reinforces preferences for social reciprocity and individual creativeness over monetary earning as well as solidarity with weaker members of the society (Kitschelt and Rehm 2014). In addition, the social and educational services of the welfare state are an important source of employment for the new middle class, making it rational for them to support its continuous expansion or, at least, resist its retrenchment.

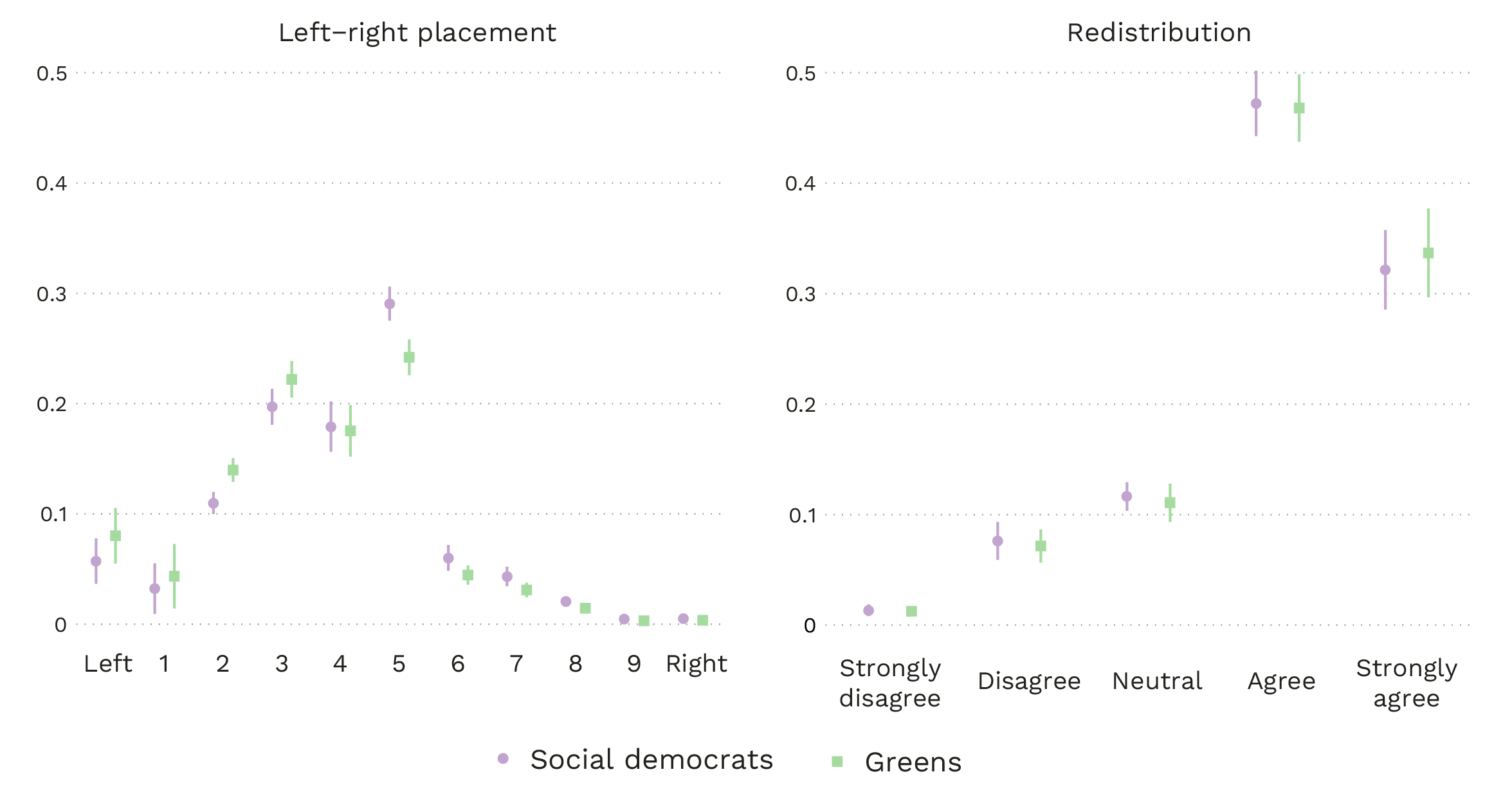

Figure 1 illustrates the support of green voters for the welfare state. Based on linear and logistic regressions with data from the 8th wave of the European Social Survey (2016) and including information from all Western European countries where green parties won more than two percent of the vote share in the national parliamentary election prior to the survey, the figure plots the predicted probabilities of the left-right self-placement of individuals as well as their attitudes towards the idea that the state should takes measure to reduce income inequality, a standard measure of redistribution preferences. The former is a general measure for ideology, which encapsulates a range of different dimensions, the latter measures whether respondents are left-wing in a narrower, economic sense. We contrast the values of green voters with those of social democratic voters, traditionally the main party of the left and the traditional defender of the welfare state, to assess whether the rise of green parties represents a threat to the welfare state.

Figure 1: Predicted probabilities of left-right placement and support for redistribution by partisanship

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto · Data source: Bremer and Schwander (2022)

Notes: The figure shows the predicted left-right placement and support for redistribution in 12 West European countries for voters who supported social democratic or green parties in the last national election. Predicted probabilities are estimated based on regression models that include country-fixed effects and country-clustered standard errors.

The figure clearly demonstrates that green voters do not place themselves more to the right than social democratic voters (left-hand panel) nor are they less supportive of redistribution than voters of the old left (right-hand panel). Hence, in line with the arguments outlined above, green voters do indeed consider themselves left-wing and generally support state-interventionist economic policies, much like voters of social democratic parties. Hence, we conclude that green voters do not wish to dismantle existing welfare state arrangements on redistribution.

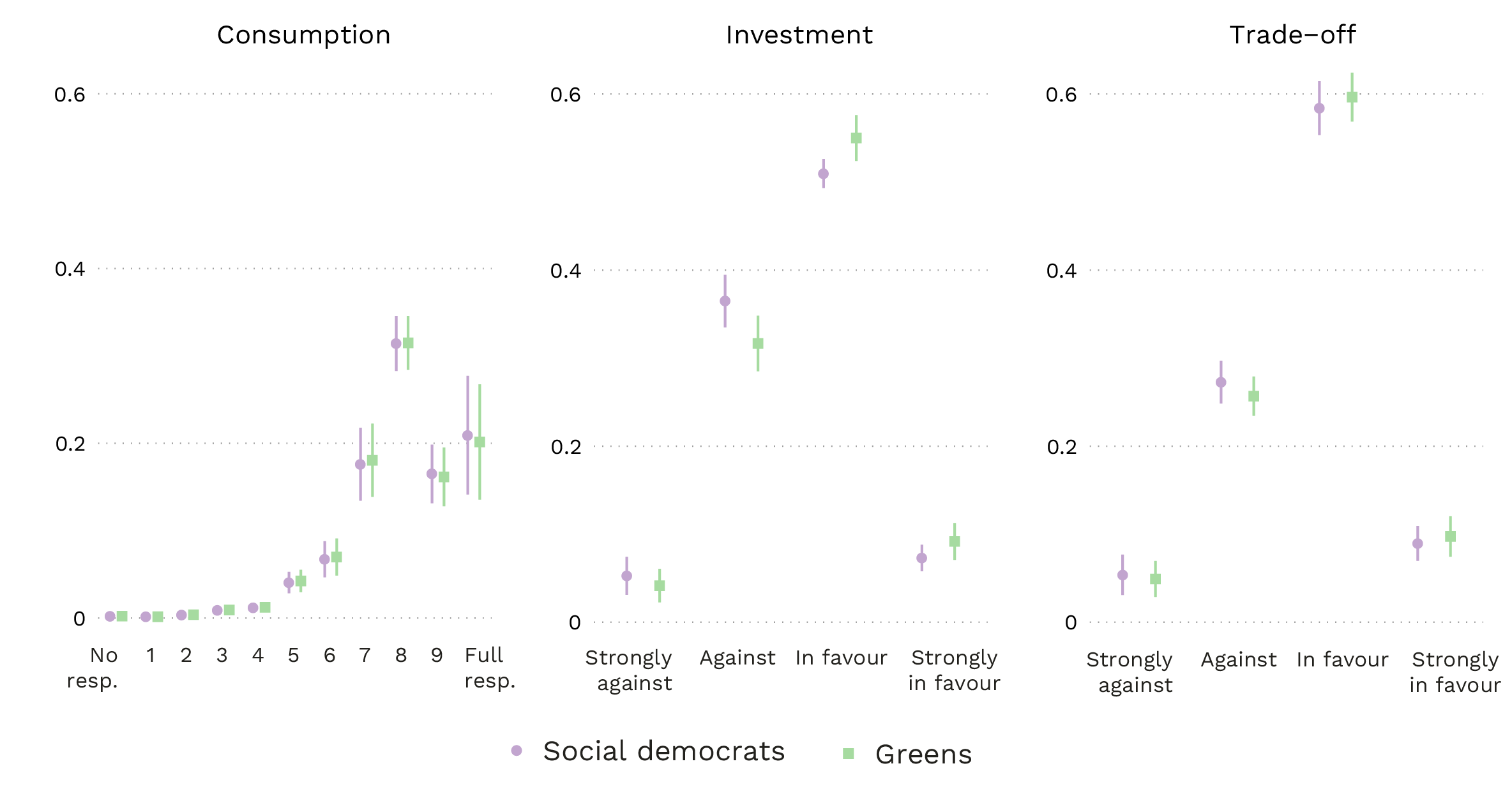

Yet, today, welfare state politics is not (only) about more or less welfare state, but very much about the goal of the welfare state: Should the welfare state enable citizens to participate in the post-industrial economy by investing in their employability and removing employment obstacle or should he compensate their income in case of employment loss? The first vision of the welfare state corresponds to a social investment welfare state, while the second vision emphasizes the welfare state’s compensatory function (Beramendi et al. 2015). A nuanced version of the myth about the rise of the green as a threat to the welfare state claims that while green voters might be in favor of the investive function of the welfare state, they oppose its protective side. Figure 2 refutes this argument, too. Based on the same data and logistic regressions, the figure shows the predicted probability of support for social investment and consumption of green and social democratic voters.

We clearly see that green voters are, indeed, somewhat more supportive of social investment than social democratic voters (see middle panel) but their support for consumption is only marginally lower than for social democratic voters and differences are not significant. In addition, the right-hand panel of Figure 2 shows to which side green and social democratic voters sway when confronted with a trade-off between investing in the training of the unemployed or compensating their income loss. Such a trade-off question reflects today’s reality of welfare state policy-making more accurately than the simple questions used above, as welfare politics has often become a zero-sum game in our times of permanent austerity (Häusermann et al. 2021). Both politicians and voters have to decide which aspects of the welfare state should be maintained or even expanded, often at the expense of other aspects of the welfare state. Considering such a trade-off scenario, we see that green voters are not more likely to support social investment than social democratic voters when there is a trade-off between spending on social consumption and social investment. Overall, the results suggest that green voters support an investment-oriented welfare state but not necessarily at the expense of consumption.

Figure 2: Predicted probabilities of support for consumption and investment by partisanship

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto · Data source: Bremer and Schwander (2022)

Notes: The figure shows the predicted levels of support for different social policies in 12 West European countries for voters who supported social democratic or green parties in the last national election based. Predicted probabilities are estimated based on regression models that include country-fixed effects and country-clustered standard errors.

Supply side: The welfare state as a salient issue for green parties in Europe

The second part of the argument on the rise of green parties as a threat to the welfare state concerns the supply side of politics. It states that green parties do not care about distributive politics, even if their voters do. They are viewed as political entrepreneurs politicizing issues on the second, cultural dimension of politics such as the environment, minority rights or migration (Hobolt and de Vries 2022, Meguid 2005). In the following section, we argue and demonstrate that green parties are welfare-state friendly parties, too, and that the welfare state is a salient issue to them.

Admittedly, as children of the new social movements in the 1960s and 1970s, new value issues are of great importance to green parties. Not only voters, but also party officials and activists value the individual liberty to choose an autonomous lifestyle. They advocate women’s emancipation and gay rights, decentralized modes of political decision-making as well as pacifism and multiculturalism (Kitschelt 1989, Poguntke 2019). Yet, this emphasis on individual liberty is reflected in green parties’ positions towards the welfare state as well. In contrast to accounts that consider green parties a purely cultural force that centers their electoral appeal on cultural issues alone, welfare state issues are clearly important for the ideological appeal of green parties, and increasingly so. Based on data from the Comparative Manifesto Project, Figure 3 shows that the welfare state is an important issue in the electoral platforms of green parties. In particular since the 2010s, green parties have even emphasized distributive issues in their electoral platforms more than, for example, social democratic or liberal parties. If we consider parties as representatives of their electorate, keen to implement their voters’ interest in politics, that focus of green parties on distributive issues is plausible. As green parties tend to enter government as part of a left coalition, their attention to distributive issues also makes sense from a coalition perspective. Indeed, research on the effect of green government participation has shown that the inclusion of green parties in national governments leads to higher spending on social investment, while the status quo prevails regarding spending on social consumption (Roeth and Schwander 2021).

Discussion and implications

This research brief dismantles the concern that the rise of green parties threatens the welfare state because green voters are argued to be economically conservative due to higher education and social position, or because green parties do not care about the welfare state. Based on recent research on the welfare state politics of green parties, this research brief refutes both arguments as a myth. The research brief highlights the compatibility of green voters’ preferences with a progressive welfare state agenda (see also Matthias Enggist’s research brief on the rejection of welfare chauvinism among green and social democratic voters) and underscores the importance of welfare state issues for green parties.

More specifically, the research brief demonstrates that green voters consider themselves left-wing and generally support state-interventionist economic policies, much like voters of social democratic parties. When it comes to redistribution specifically, green voters do not wish to dismantle existing welfare state arrangements. Regarding the trade-off between a social investment or social consumption orientation of the welfare state, green voters are very supportive of social investment, but not at the expense of social consumption. Taken together, our results imply that green voters generally support state-interventionist economic policies, much like voters of social democratic parties, and their rising numbers therefore strengthens the pro-welfare state voter coalition. The research brief also emphasizes that the welfare state is a salient issue to green parties, both in their electoral platforms but also when in government.

With this, the research brief demonstrates that the numerical decline of the traditional core electoral constituency of progressive parties, blue-collar workers, does not necessarily entail a weakening of progressive politics and redistributive economic policy. This is also important because it refutes the idea of a trade-off between culturally progressive and economically progressive politics (see also the research brief “The myth of a divided left” by Silja Häusermann and Tarik Abou-Chadi). Rather, the evidence outlined in the research brief suggests that a sizable share of middle class voters are drawn to parties appealing to both economic equality and redistribution and to socio-cultural inclusion and sustainability. In sum, the research brief shows that new coalitions in support of a progressive welfare state agenda are possible and effective.

Based on:

Bremer, Björn and Hanna Schwander. 2022. The Distributive Preferences of Green Voters in Times of Electoral Realignment, working paper.

Röth, Leonce and Hanna Schwander. 2021. “Greens in government. The distributive policies of a culturally progressive force”. West European Politics, 44(3): 661-689.

References:

Beramendi, Pablo, Silja Häusermann, Herbert Kitschelt, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2015. The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dolezal, Martin (2023). Die Schweizer Grünen im europäischen Vergleich, in: Die Grünen in der Schweiz. Entstehung, Wirken, Perspektiven. Sarah Bütikofer und Werner Seitz (Hrsg). Zürich: Seismo.

Kitschelt, Herbert and Philipp Rehm. 2014. Occupations as a site of political preference formation. Comparative Political Studies, 47(12), 1670–1706.

Oesch, Daniel. 2006. Redrawing the Class Map. Stratification and Institutions in Britain, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Kitschelt, Herbert 1994. The Transformation of the European Social Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kriesi, Hans-Peter. 1998. The transformation of cleavages politics: The Stein Rokkan lecture. European Journal of Political Research (33), 165–185.

Note: This article was published as a research brief by PPRNet.

Image: flickr.com