Why fiscal social democratic parties do not benefit from orthodox fiscal policies

Björn Bremer

12th July 2024

The myth of fiscal orthodoxy as a winning strategy for the center-left

In an era of permanent austerity, social democratic parties have struggled to develop a clear economic program. There has been a widespread belief among the center-left that progressive forces need to adopt fiscal orthodox policies to shore up their fiscal credibility. Especially in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), social democrats were complicit in Europe’s austerity settlement. As government debt became perceived as a salient problem following the Greek sovereign debt crisis in 2010, they supported the turn towards fiscal consolidation and often implemented austerity policies themselves.

The COVID-19 pandemic put an end to any pretense that austerity was desirable, as governments had little choice but to support workers and businesses in the face of the economic shutdown. However, following the pandemic, social democratic parties are again struggling to define their narrative on fiscal policies. For example, even before markets revolted against the fiscal plans by the short-term British prime minister Liz Truss, the Labor Party promised “ironclad discipline” on public finances. Its leaders have set out fiscal rules that would bind a future Labour government. Similarly, the German SPD has been reluctant to full-heartedly embrace policies that would address Germany’s chronic underinvestment, as it remains committed to the constitutional debt brake (Schuldenbremse), which the party helped to establish in 2009.

Commitment to such fiscal rules, however, is difficult to square with other, central programmatic commitments of the center-left. Especially in the face of accelerating climate change, progressive political forces are faced with a difficult situation: How can they mobilize sufficient public resources to support the green transition without sacrificing the welfare state that they helped to build in the 20th century? Worried about appearing as fiscally irresponsible, center-left leaders force themselves to make difficult trade-off. As the leader of the Labour Party Keir Starmer himself wrote in an op-ed in December 2023:

There will be many on my own side who will feel frustrated by the difficult choices we will have to make…This is non-negotiable: every penny must be accounted for. The public finances must be fixed so we can get Britain growing and make people feel better off.i

Irrespective of the doubtful claim that ironclad fiscal rules will make people feel better off economically, this research brief argues that such strategies are driven by a political myth: The belief that it is electorally advantageous for social democratic parties to adopt orthodox fiscal policies.

This myth comes in two forms. First, in its weaker form, there is a misconception that orthodox fiscal policies help social democratic parties establish their fiscal credibility and increase their electability. Believing that the path to power leads through the center, social democratic parties have been concerned about establishing their economic competence in the eyes of (centrist) voters for decades. But economic competence is not simply acquired by repeating arguments by the right. Especially in fragmented party systems, it is profoundly important for social democratic parties to adopt fiscal policies that are in line with their overall program; otherwise, the positions that social democrats adopt are not considered credible.

Second, a stronger version of the myth suggests that actually implementing orthodox fiscal policies does not backfire electorally for social democratic parties. This argument suggests that austerity policies are popular among voters and that center-left parties, like other parties, can implement them without incurring any electoral losses. But austerity policies often have real economic costs, and especially when their key constituencies are hurt, social democratic parties are likely to incur the wrath of voters when they implement such policies.

Debunking the myth: It is not electorally beneficial for social democratic parties to adopt orthodox economic policies

In the last few decades, many social democratic parties have embraced orthodox fiscal policies. Especially when the immediate “firefighting phase” in response to the GFC was over, social democratic parties were complicit in the turn towards austerity. After Greece had requested its first bailout in 2010, the salience of government debt dramatically increased. It became one of the most important economic problems of the time, giving deficit spending a bad name. In this context, the center-left accepted austerity as a necessary evil in many countries across Europe.

One of the main reasons for this choice was the perceived electoral pressure to address rising deficits. Social democrats believed that voters felt uneasy about increasing levels of government debt. Even in countries that faced little or no economic or institutional pressure to pursue austerity, social democrats embraced fiscal consolidation because they faced a common problem: The need to establish their claim to be competent managers of the economy.

Social democrats essentially believed that they faced a dilemma: Some of their most important aims, including the protection and expansion of the welfare state and reduction of inequalities, may be popular but lack fiscal credibility. Especially in countries like Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom (UK), where the center-left had been in government before and during the financial crisis, parties believed that they had to re-establish their perceived economic competence. Receiving most of the blame for the crisis, they tried to establish their hawkish credentials. They often went above and beyond to emphasize that they would responsibly manage the economy in ways that did not harm long-term growth. This led them to join the chorus of austerity, agreeing with the organizing political assumption that debt had to be reduced.

Put differently, social democrats responded to the exceptional salience of government debt, believing that fiscal credibility was a necessary condition to win elections. And, indeed, sometimes this strategy worked. Most famously, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown won a landslide electoral victory in 1997 with an orthodox fiscal policy; they promised to follow strict fiscal rules and pledged to maintain the Conservatives’ spending plans for two years. However, research shows that often the strategy does not work for two reasons.

First, adopting orthodox fiscal policies creates inconsistencies and contradictions within the economic program of social democratic parties. Like other progressive forces (see Hanna Schwander and my research brief “Why the rise of green parties does not threaten the welfare state”), they support the welfare state and aim to make capitalism socially acceptable by limiting its excesses through state intervention. Austerity, however, threatens the sustainability of the welfare state and undermines the capacity of the state to correct market outcomes. This gives many people the impression that social democracy is an empty and obsolete term. It contributes to a process that can be called “brand dilution” (Lupu. 2016), as austerity forces parties of the left to water down their historic commitment to protect the weakest members of society.

Second, by endorsing austerity, social democratic parties effectively turn fiscal consolidation into a valence issue. They attempt to neutralize the topic by shifting towards the center and imitating their opponents’ position. However, rightly or not, social democrats are perceived as less competent when it comes to managing the public’s finances. Given their other programmatic commitments, their support for fiscal consolidation often lacks credibility. But by bowing to the general presumption that austerity is necessary, social democrats still legitimize arguments that fiscal consolidation is necessary. This gives the center-right a strategic advantage when social democratic parties agree on the need to reduce the deficit: It does not only enable them to claim that they support the “right” economic policies, but also insist that they are “better” at implementing them.

The result is twofold. On the one hand, fiscally conservative voters in the center are unlikely to vote for social democratic parties, despite the parties’ support for budgetary rigor. To the extent that these voters care about fiscal consolidation, they are more likely to vote for center-right parties who traditionally own the issue of budgetary rigor.

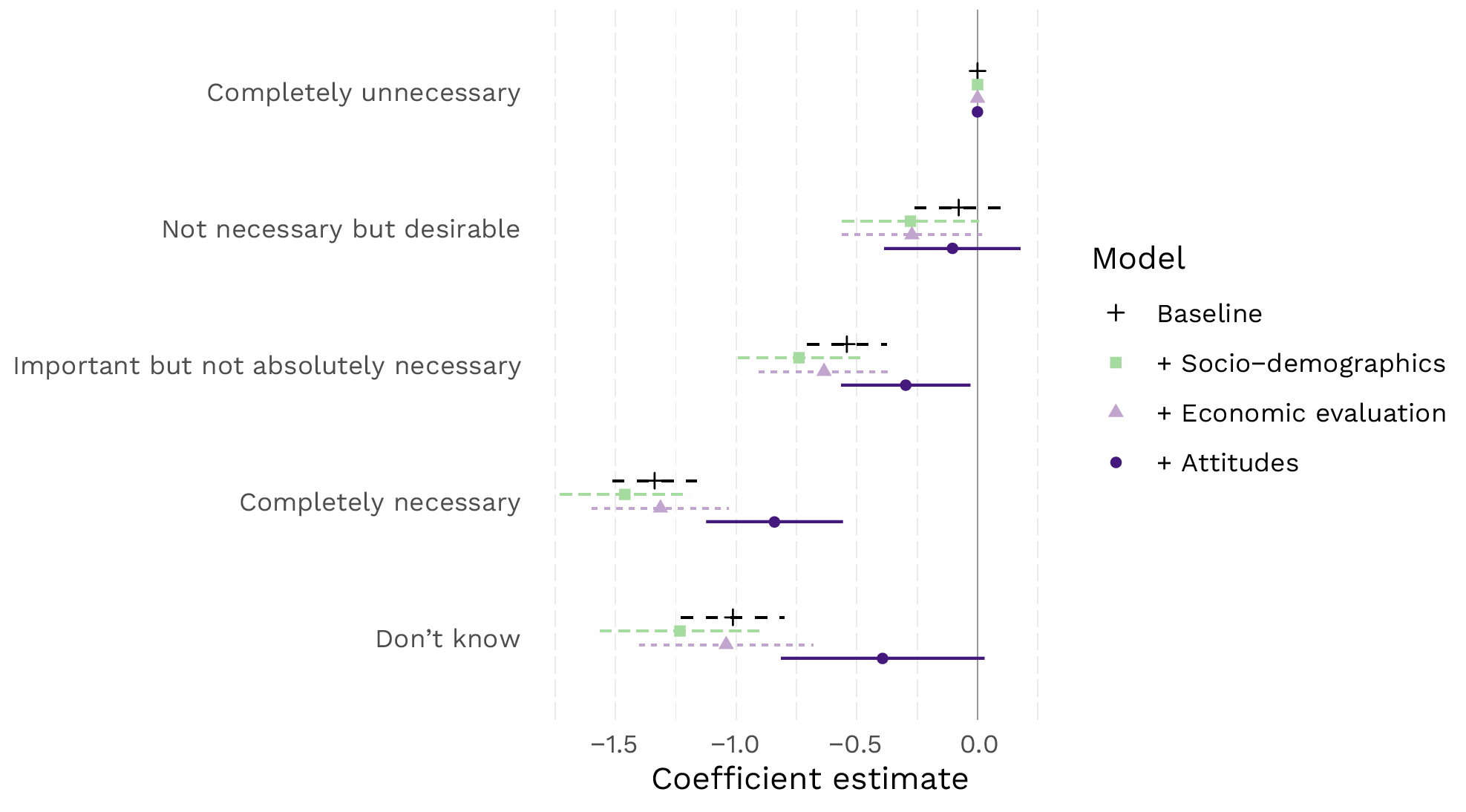

This is illustrated by evidence from the British electoral campaign in 2015 when the Labour Party adopted a triple “budget responsibility lock” on the first page of its manifesto. Its leaders promised that all their policies were fully funded and that they would get the national deficit and debt down. Yet, Figure 1 based on data from the British Election Study (BES) shows that respondents who thought that deficit reduction was necessary or important were less likely to vote for the Labour Party than people who thought that it was unnecessary (the reference category). In fact, there is a monotonically increasing pattern in Figure 1: People who were more concerned about the deficit were less likely to vote for Labour, despite their “budget responsibility lock”.

Figure 1: Estimated correlation of attitudes towards the budget deficit and the propensity to vote for the Labour Party ahead of the 2015 election

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto — Data source: Bremer (2023, ch. 8) based on the British Election Study.

Notes: The figure shows estimated regression coefficients and 95 percent confidence intervals based on OLS regressions. The question wording to measure attitudes towards the deficit was as follows: “How necessary do you think is it for the UK Government to eliminate the deficit over the next three years—that is, close the gap between what the government spends and what it raises in taxes?”

On the other hand, such promises are likely to demobilize the core voters of social democratic parties, who are most likely to vote for them. These voters are often opposed to austerity policies and disillusioned by the center-left’s shift to the center. For example, ahead of the British election in 2015, people who thought that spending cuts in the UK had gone too far or much too far were, in principle, much more likely to vote for the Labour Party. Supporting such cuts undermined the party’s ability to mobilize these voters to actually turn out on election day, contributing to the party’s loss.

Therefore, austerity is not an election winner for social democratic parties. When they adopt fiscal orthodox policies during election campaigns, they often help to mainstream austerity, entrenching the notion that it is a necessary evil without gaining any electoral benefits. As long as the salience of government debt is low, they may still win with such a program (e.g., in the UK in 1997). But even when this happens, center-left parties do not benefit from this in the long run: The voters that they attract with such a centrist program often do not have a particularly strong attachment. They are swing voters who are likely to turn to other parties again in the future (Karreth et al. 2013). Since this happens at the expense of appealing to their core voters, it often invites internal strife and shrinks the size of party loyalists. Therefore, it is a myth that social democratic parties benefit electorally from embracing fiscal consolidation.

Social democratic parties lose when they implement (certain forms of) orthodox fiscal policies

A stronger version of the myth holds that social democratic parties are not punished, maybe even rewarded, when implementing fiscal orthodox policies. This relies on similar arguments as outlined above but it emphasizes two additional points. First, it suggests that centrist voters actually reward social democratic parties for fiscal prudence. They care enough about lowering government debt that they are happy to accept spending tax and/or tax increases, rewarding parties that implement these policies. Second, social democratic voters opposed to austerity policies are still voting for these parties even if they implement austerity policies. Especially in majoritarian electoral systems, voters may simply have nowhere else to go, as there is only one major progressive party. In proportional electoral systems, voters may be loyal enough not to defect. Center-left voters thus swallow the bitter pill of austerity due to a lack of alternatives, loyalty, or both.

However, an increasing amount of research shows that this is not true. For example, Figure 2 shows the effect of austerity packages on the popularity of social democratic parties across twelve Western European countries from 2005 to 2017. Using time-series analyses based on monthly opinion polls, it shows that when social democratic parties are in government and announce an austerity package, their approval ratings on average fall by 1 percentage point afterwards. This effect is statistically significant and larger than for center-right parties. Moreover, given that governments often announce several austerity packages within the span of a few months or even weeks, the effect is sizeable.

Figure 2: Average marginal effect of austerity on support for social democratic parties by incumbency

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto — Data source: Bremer (2023, ch. 8) based on own data collection and coding.

Notes: The figure shows the average marginal effect and 95 percent confidence intervals, estimating the correlation between austerity packages and the popularity of social democratic parties based on whether they are in government or in opposition. It is based on all austerity packages announced by governments from 2005 and 2017 in 12 European countries. The countries included in the analyses are Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, and the UK.

The electoral costs of austerity are confirmed by evidence data that goes back further in time. Based on data from sixteen advanced economies from 1978 to 2014, analyses show that the social democratic vote share is significantly lower in elections following fiscal consolidations that they implemented. This is in line with other research that shows that austerity packages often lead to polarization (Fetzer 2019; Hübscher et al. 2023). It suggests that “austerity from the left” is politically risky for social democratic parties. Especially, in the 2010s, it contributed to the deep electoral crisis that social democratic parties experienced.

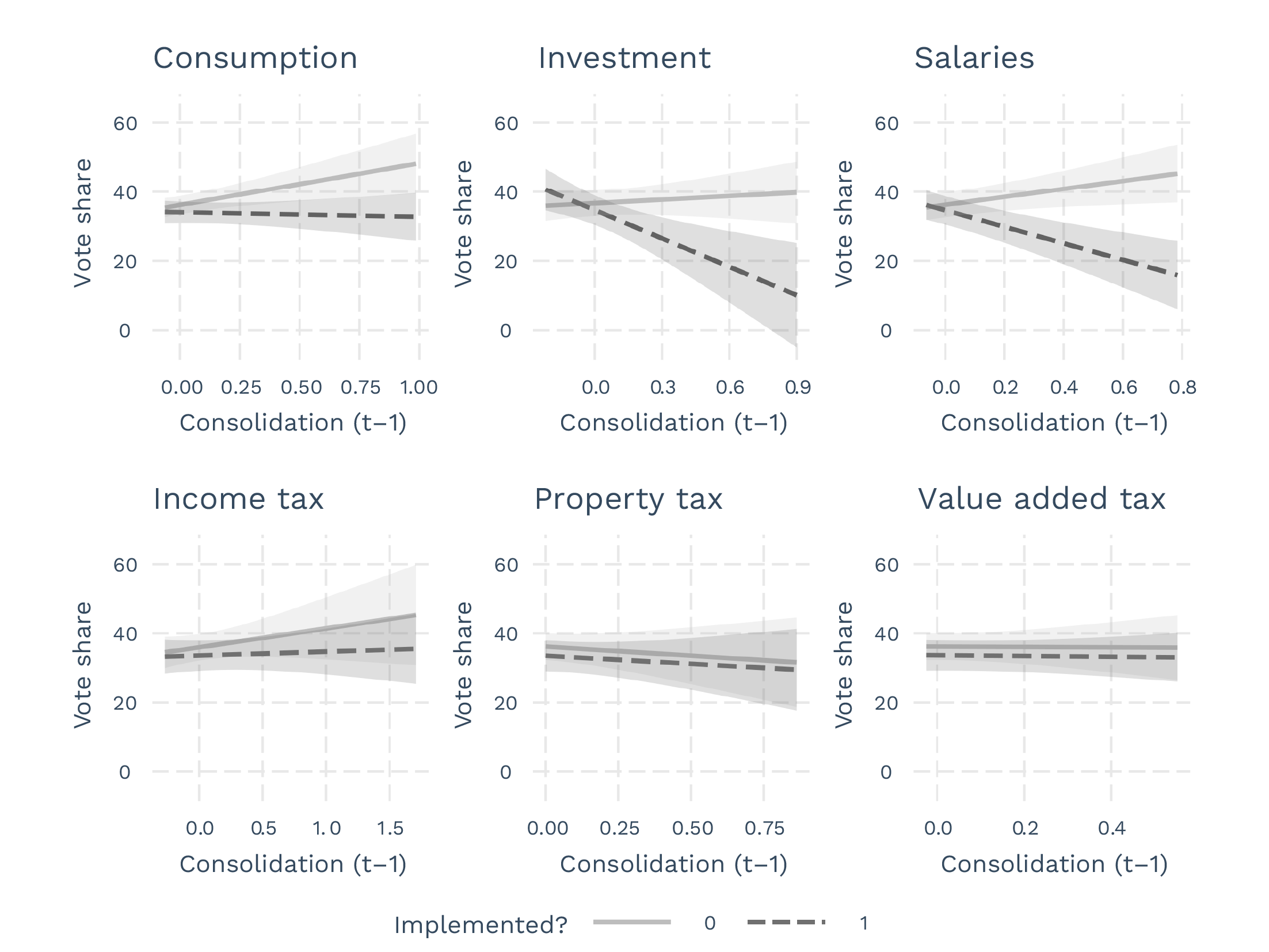

However, as Figure 3 shows, not all fiscal consolidations are equal: Social democratic parties lose particularly badly when they themselves implement spending-based consolidations that cut investment spending or public sector wages, which hurt some of their most important constituencies (educated middle-class voters and public sector workers, respectively).ii In contrast, fiscal consolidations centered around tax increases are not associated with such losses. Electorally, this gives the center-left an opening to raise revenues and pursue revenue-based consolidations: They are likely to get away with revenue-based consolidations, especially when relying on progressive tax increases. Spending-based consolidations, and particularly those that hurt key constituencies of social democratic parties, tend to be very costly for social democratic parties, though.

Figure 3: Predicted vote share of social democratic parties by the level of consolidation in different areas and incumbency status

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto — Data source: Bremer (forthcoming) based on data from Alesina et al. (2019)

Notes: This figure shows the predicted effect of spending cuts or tax increases in different areas in the year before an election on the electoral performance of center-left parties in that election, depending on whether they were in government at t-1 or not. The countries included in the analyses are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, Italian, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United States.

Discussion and implications

Today, social democrats are often hamstrung by concerns about electability. They believe that they have to adopt orthodox fiscal policies to increase their fiscal credibility, which limits their ability to develop transformative economic policies. This research brief argued that this reasoning is based on a common myth that social democratic parties benefit from adopting orthodox fiscal policies. Instead, “austerity from the left” harms the electoral prospects of social democratic parties and is likely to be punished when implemented.

Evidence that centrist policies are vote maximizing stems from periods during which the advanced economies experienced booms and relative stability (e.g., the post-war period and/or the Great Moderation). In times of economic upheaval and recurring crises, which have shaped much of the advanced economies since the GFC, this strategy is unlikely to be successful. In moments like these, fiscal policies involve myriad trade-offs and voters are unlikely to prioritize getting debt under control (Bremer and Bürgisser 2023). Instead, they expect progressive parties to demonstrate an ability to protect the weakest members of society, pushing for an active state and long-term structural reforms that reign in markets and correct undesirable market outcomes such as rising inequalities (also see Macarena Ares’ research brief on “A progressive service-class coalition” for welfare state preferences within the working classes and Matthias Enggist’s research brief “Why welfare Chauvinism is not a Winning Strategy for the left” on left voters attitudes towards a welfare chauvinistic welfare state).

Therefore, the public —and especially the social democratic electorate— may be open to more spending arguments and debt tolerance than commonly argued. Especially given that fiscal policies are a technical issue, salience and voters’ preferences and priorities are influenced by elite narratives and frames (Barnes and Hicks 2018; Bisgaard and Sloothus 2018). In the face of rapid climate change, technological progress, and economic stagnation, progressive parties have room for maneuver: They can build an electoral coalition of voters who believe that public investment, a strong welfare state, and functioning public services are badly needed. Certainly, this task should be easier than the alternative: To put forward a contradictory program – promoting austerity but claiming to protect public services and the welfare state – and hope that voters are ready to believe such fairytales. This strategy failed in the 2010s, and it is likely to fail again.

i Source: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2023/12/02/voters-have-been-betrayed-on-brexit-and-immigration/

ii Social democratic parties often avoid cutting consumption spending, which is why the results for this type of spending must be interpreted cautiously.

Based on:

- Bremer, Björn. 2023. Austerity from the Left: Social Democratic Parties in the Shadow of the Great Recession. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bremer, Björn. Forthcoming. “The electoral consequences of centrist policies: Fiscal consolidations and the fate of social democratic parties.” In Häusermann, Silja and Kitschelt, Herbert (eds.), Beyond Social Democracy: The Transformation of the Left in Emerging Knowledge Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

References:

-

Alesina, Alberto, Carlo Favero, and Francesco Giavazzi. 2019. Austerity: When it Works and when it Doesn’t. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020.

-

Barnes, Lucy, and Timothy Hicks. 2018. “Making austerity popular: The media and mass attitudes toward fiscal policy.” American Journal of Political Science 62(2):340–354.

-

Bisgaard, Martin, and Rune Slothuus. 2018. “Partisan elites as culprits? How party cues shape partisan perceptual gaps.” American Journal of Political Science 62(2):456–469.

-

Bremer, Björn, and Reto Bürgisser. 2023. “Do citizens care about government debt? Evidence from survey experiments on budgetary priorities.” European Journal of Political Research 62(1):239–263.

-

Fetzer, Thiemo. 2019. “Did austerity cause Brexit?” American Economic Review 109(11):3849–3886.

-

Hübscher, Evelyne, Thomas Sattler, and Markus Wagner. 2023. “Does austerity cause polarization?” British Journal of Political Science 53(4):1170–1188.

-

Karreth, Johannes, Jonathan T. Polk, and Christopher S. Allen. 2013. “Catchall or catch and release? The electoral consequences of social democratic parties’ march to the middle in Western Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 46(7):791–822.

-

Lupu, Noam. 2016. Party Brands in Crisis: Partisanship, Brand Dilution, and the Breakdown of Political Parties in Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Note: This article was published as a research brief by PPRNet.

Image: unsplash.com