Introduction

The “gig economy”—in which online platforms such as Uber, Upwork and Deliveroo enable individuals to sell services—has developed at different speeds in different countries. A convincing explanation for this phenomenon is the varying scope and omnipresence of technological development in different countries, and the size of their tertiary sector (their degree of “tertiarization”). However, it has already been pointed out that technology and structural economic factors are not the only determinants of the spread of “platform work”.

Generally, platform work is characterized by great flexibility, which is sometimes sought by workers, who can decide when to make themselves available to the platform. Yet studies show that the flexibility is often imposed on workers, rather than chosen by them, and that in reality those who take work in the gig economy have few alternatives. Platform work may be accessible, but has little to offer in terms of income, job security and social protection.

Our study examines the impact of social and educational policies on the growth of this form of work.

The research process

Our main hypothesis was that decisions to engage in platform work depend on the availability of alternatives, and that the extent to which individuals have alternatives available to them is dependent on the success of social and educational policies in attaining three major goals: 1) protecting individuals and families against poverty; 2) enabling parents to reconcile work and family life; and 3) facilitating the transition from education to employment.

We tested our hypotheses using a sample of 21 European countries. We obtained the main dependent variable from two major surveys of platform work carried out in 2018 and 2020 (known as COLLEEM II 2018 and ETUI IPWS 2020). Unfortunately, Switzerland is not included in these databases. Swiss data on platform work, collected by the Federal Statistical Office, do exist, and show a very low prevalence of this form of work. However, these data are not comparable with those that we used.

Results

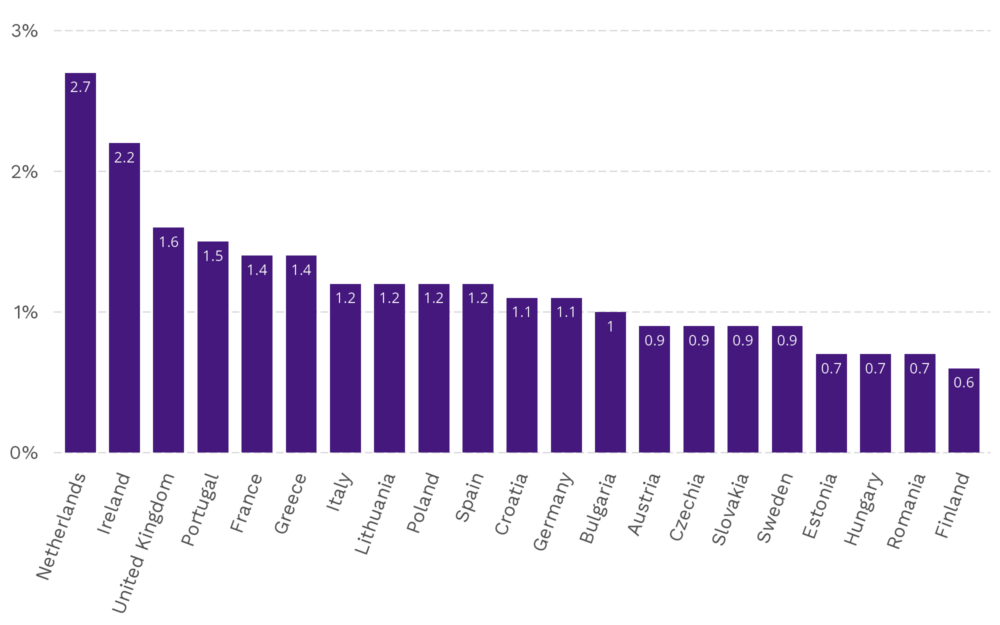

Figure 1 presents a descriptive data analysis. It suggests that welfare regimes (or other related institutions) play a part in explaining the variations between the rates of platform work in different countries. The highest prevalence of platform work is found in liberal welfare states (United Kingdom, Ireland). In contrast, Nordic countries, whose welfare states quite efficiently fulfil the three functions on which our study focused, show the lowest rates of this type of work. Eastern and Southern Europe lie somewhere between the two, and continental European countries show relatively low levels of platform work, with the exception of the Netherlands, which has the highest rate. We think that the Netherlands could be considered as an outlier in this analysis, mainly because of the historical importance of part-time work.

Figure 1. Prevalence of platform work in Europe (as a percentage of the active population) by country

Graph : Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto

We then attempted to identify the factors that explain transnational variations in the prevalence of platform work. Of the three hypotheses that we examined, it was the third that was best borne out by the data. The prevalence of platform work is highest in countries where there is a greater mismatch between the labour market and the skills of higher-education graduates.

Overall, our study suggests that platform work is not necessarily a choice that individuals make because they value the liberty and flexibility that this type of work can offer. The choice may instead be an individual response to the inadequate performance of key social and educational policies, particularly those intended to facilitate the transition from school to work.

Reference

Bonoli, G., Chueri, J., & Dimitri, C. (forthcoming). What drives the expansion of platform work ? In G. Grote, R. Guzzo, R. Lalive, & H. Nalbantian (Eds.), Interdisciplinary Foundations for Organizational Science and Application: A Dialogue between Psychology and Economics. Oxford University Press.

Picture: unsplash.com

Note: this article is taken from the ninth IDHEAP Policy Brief. It has been edited by Robin Stähli, DeFacto.