Public acceptance of climate policy depends on trust in government

Christina Toenshoff

24th April 2025

This brief summarizes empirical evidence which demonstrates that trust in the government shapes public opinion on climate policy. It argues that since climate policy always involves government intervention in some form, public acceptance of climate policy depends on the extent to which the public trusts their government to choose and implement policies fairly, effectively, free from corruption, legitimately, and credibly. Drawing on survey evidence, I demonstrate that trust in the government is strongly positively correlated with public support for various climate policies, such as carbon taxes and a ban on coal-fired power plants. I further show that those who trust the government react more positively to policy measures that aim to compensate the vulnerable for the cost of climate policy. Finally, I discuss policy measures that might increase political trust and thus support for climate policy. Among others, these include anti-corruption measures and broader participation by citizens.

Climate policy preferences and the role of trust in government

Even though in many countries voters are becoming increasingly concerned about climate change, specific climate policies are often unpopular and can face public backlash. Social scientists have studied several important reasons for this backlash – from policies’ distributional consequences to doubts about the accuracy of climate science. In this brief, I focus on another important aspect that research has shown to shape public acceptance of climate policies: trust in the government. All climate mitigation policy requires some government intervention in the economy as the government has to steer consumption and production away from polluting industries or encourage the growth of less polluting alternatives. Individuals are more likely to accept this increased role of the government in steering markets if they trust that their government implements policies well.

Government intervention to combat climate change can look very differently across countries and policy contexts. Governments might directly regulate how much carbon certain actors can emit or put a price on emissions. They might ban certain technologies that are not climate-friendly or incentivise the purchase of greener alternatives with subsidies. Recently, governments have started pursuing green industrial policies aiming to grow green sectors within their economies. Climate policy is also often accompanied by compensation for vulnerable actors who bear the cost of climate action. Regardless of the details, effective climate policy tends to mean that the role of the state in managing the economy grows.

As such, whether or not the public accepts climate policy depends greatly on whether they trust the government to choose and implement such policies well. That means that the public must believe that the government has the capacity to implement policies efficiently, fairly, and free from corruption. It also means that citizens must trust that policy instruments will be chosen in a politically legitimate way. Lastly, it implies that climate policy is credible, meaning that citizens can trust the government to stick to long-term policies once they have been promised. (For a more detailed discussion of the role of credibility in public opinion regarding compensation policies, see Edenhofer and Genovese’s policy brief.)

This brief presents multiple pieces of evidence to support the claim that trust in the government shapes support for climate policy. First, I draw on experimental and observational survey evidence to show that political trust moderates support for climate policies that aim to reduce carbon emissions, such as fossil fuel taxes and a ban on coal in energy production. Next, I demonstrate that trust in government also influences how the public reacts to policies that compensate households for the cost of climate policy. Finally, I draw on others’ work to discuss what policymakers could do to increase public support for climate policies by enhancing the public’s trust in the government.

Trust in government increases support for climate policy

Social science research, both experimental and observational, has found extensive evidence that political trust is strongly related to attitudes toward climate policy. Malcolm Fairbrother (2016) provides a compelling overview of research findings regarding different types of trust. He concludes that distrust in politicians is “ubiquitous” and can make even those who believe in science and are concerned about climate change oppose government action.

Indeed, based on the European Social Survey, Fairbrother, Sevä and Kulin (2019) find that among those who don’t trust the government, belief in climate change does not lead to more support for climate policy. Only among those with a relatively high level of political trust is belief in climate change positively associated with support for climate policy. Thus, without political trust, persuading the public that climate change is real is not sufficient to create support for policy measures.

Research has also studied what shapes trust in the government, which will be discussed in more detail at the end of this brief. One unsurprising factor is the quality of a country’s institutions. Davidovic and Harring (2020) measure this quality using three variables from the International Country Risk Guide: corruption, law and order, and bureaucratic quality. They then compare public opinion across 23 European countries and show that political trust is an intermediate step between the quality of institutions and public opinion on climate policies. The better the quality of political institutions, the higher the average level of political trust in the population, and the greater the acceptance of climate policies.

Much work on trust has focused on specific types of climate change policy. This literature has found especially strong evidence of a positive relationship between political trust and support for carbon taxes (e.g., Hammar and Jagers 2006; Davidovic and Harring 2020). What is more, experimental survey evidence has shown that measures to make carbon taxes more palatable, such as tax cuts in other areas, are ineffective if individuals distrust the government (Fairbrother 2017).

To add to this already substantial evidence on the relationship between political trust and climate attitudes, Isabela Mares, Kenneth Scheve, and I fielded a survey among a representative sample of a little over 2000 German adults in 2021. Most survey research on political trust is based on questions that ask respondents to rate their level of trust in a battery of institutions. We take a different approach and measure an important consequence of political trust: the belief that state intervention in the economy is appropriate and effective. This belief in state intervention is closely linked to trust in the government. Those who do not believe that the government can be trusted to implement policy well are unlikely to think that the government should intervene to steer the economy.

We use a set of questions initially developed for the German General Social Survey to measure support for state intervention. These questions ask about individuals’ support for six different types of intervention in domains other than the environment. The more types of intervention respondents support, the higher we can assume their trust in the government to be. It is important to note that this measure does not simply capture whether an individual leans to the left politically. Some areas of state intervention we ask about, such as maintaining price stability, are more typically supported by right-leaning voters. Further, the relationships between our measure of belief in state intervention and climate attitudes are robust to the inclusion of variables that measure left-right ideology.

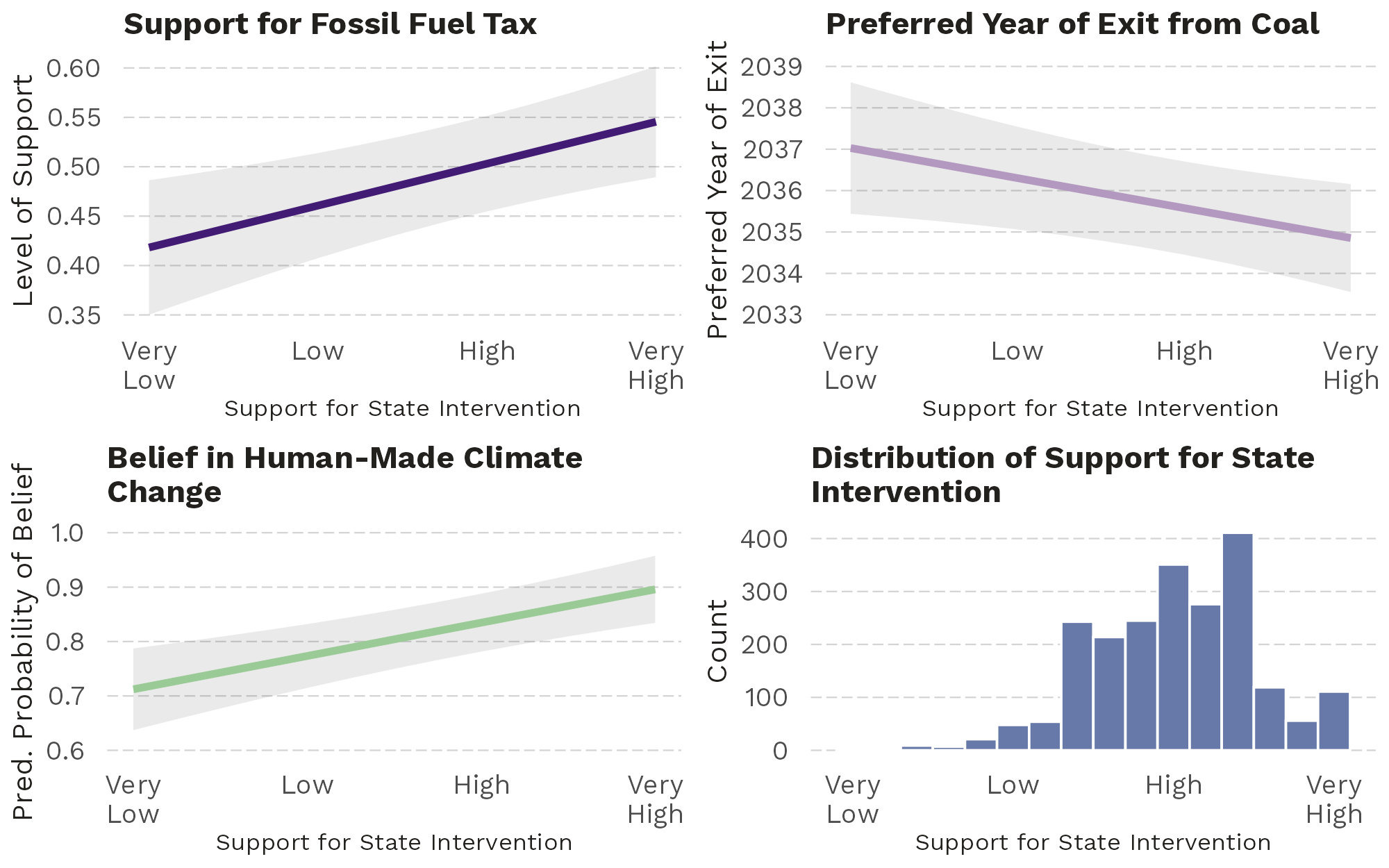

We chose Germany as our test case because it is an inherently difficult case to study trust in government. It is a country with relatively high institutional capacity and quality and, thus, high political trust. As a result, we found support for government intervention to be relatively high among our sample. The bottom right panel of Figure 1 shows the distribution of respondents’ level of support for government intervention. Most respondents show high levels of support, and very few support no form of government intervention.

Nonetheless, the variation in support for government intervention allows us to investigate how support for intervention, and thus trust in the government, correlates with support for climate policies. The top panels in Figure 1 show the relationship between our core measure for trust and support for taxes on fossil fuels (top left) and individuals’ preferred year for Germany to stop using energy generated from coal (top right). The figures depict predictions based on statistical analyses that account for demographic variables like age, region, gender, and income. The lines in the graphs show the expected level of support/preferred year for the coal exit for a 50-year-old male inhabitant of Bavaria with a middle-class income. Other demographic groups have different baseline levels of climate preferences, but the slope of the relationship between support for state intervention and climate policy attitudes is universal. Across the board, higher support for state intervention is associated with higher support for fossil fuel taxes. We also find that individuals with higher support for government intervention prefer an earlier end to coal energy and are more likely to believe in human-made climate change.

Figure 1. Survey evidence from Germany finds that trust in government and belief in human-made climate change are negatively correlated. This may be driven by a general distrust in elites, including the scientific community

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto

Taken together, all of this evidence suggests that political trust shapes public opinion on climate policies. This matters for climate outcomes if politicians are responsive to public pressure. While it can be difficult to link public opinion to policy decisions conclusively, Fairbrother (2016) lists a number of empirical studies that have demonstrated that public backlash against climate policies can translate into climate-policy reversals, the rejection of climate policies in referenda and the election of less climate-friendly governments. Thus, a lack of political trust, which causes a lack of public acceptance, can seriously obstruct effective climate policies.

Trust in government increases positive reactions to compensation policies

The previous section has shown evidence of the relationship between support for policies that reduce emissions and political trust. Beyond policies that decrease emissions, governments often add policies that compensate the potential losers of climate measures. The hope is that climate action will be more palatable if done justly. For a more detailed discussion of the conditions under which compensation raises support for climate action, see Edenhofer and Genovese’s brief on the topic. Their brief argues that credibility is one crucial condition for compensation to increase the acceptance of climate policy. Credibility, here, is defined as trust that the government will keep its promises in the medium and long term.

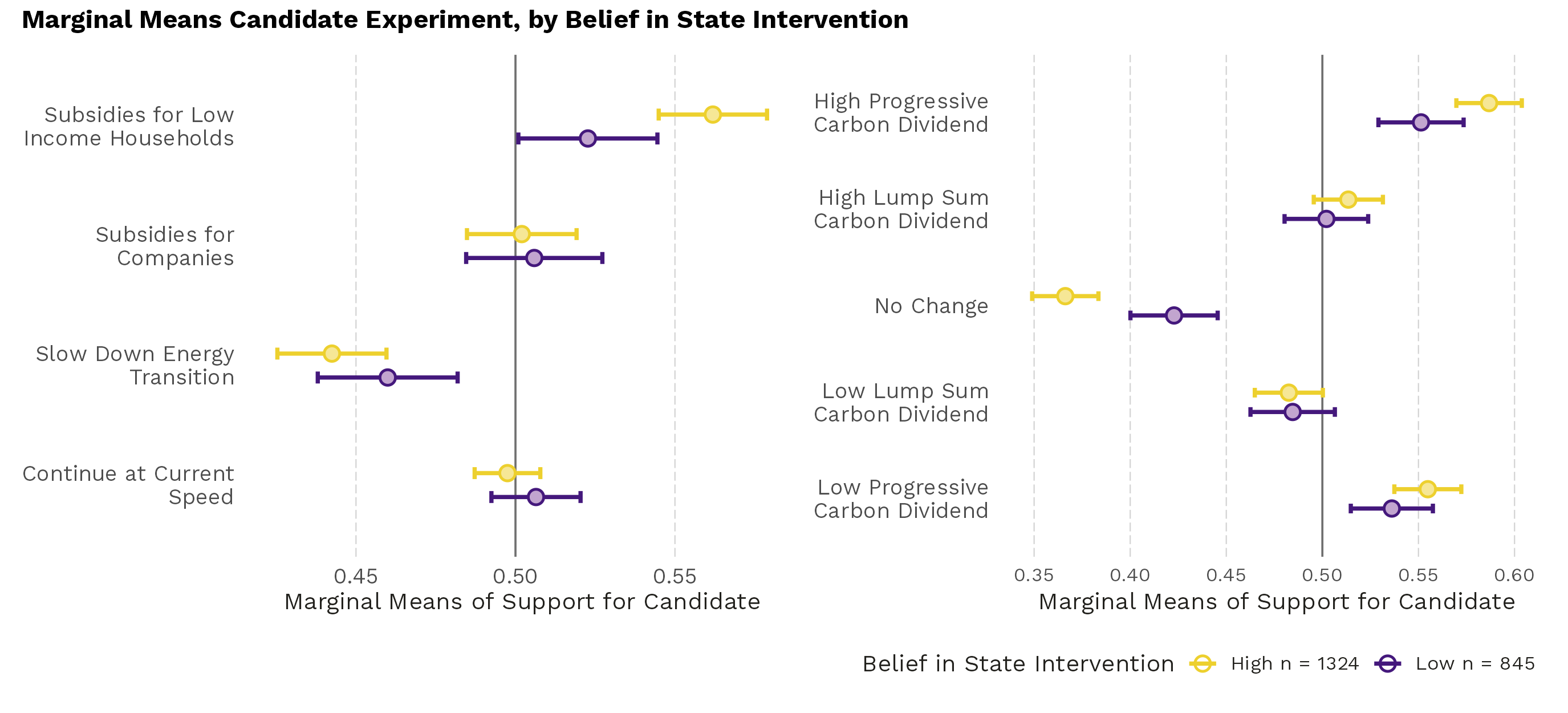

Based on this definition, it is clear that credibility is one part of overall trust in the government. In the previously cited survey in Germany, we show more generally that trust in the government shapes how the public reacts to compensation, specifically compensation for households who might face higher energy costs due to climate policies. Again, we proxy government trust by measuring participants’ support for state intervention in the economy. Our survey contains several experiments that test how participants react to different types of compensation. The first experiment, the results of which are shown on the left side of Figure 2, asks participants to choose between two political candidates. Among other things, we vary what kinds of energy policies they propose: Continuing the energy transition at the current speed, slowing down the energy transition, providing subsidies for companies with high energy costs, and subsidising the energy costs of low-income households. The left-hand figure shows the average likelihood that participants chose a candidate with different energy policy proposals. In general, slowing down the energy transition is unpopular with German voters, while compensation for high energy costs that targets lowincome households increases overall support for political candidates. However, this effect is much stronger among those who believe in state intervention, marked here in black.

In a second experiment, we test which types of compensation for households are most popular. To do so, we ask participants to choose between two climate policy plans and, among other attributes, randomly vary the kinds of compensation for households the plans entail. The results are shown on the right-hand side of Figure 2. Overall, plans that offer no compensation are much less popular than plans that offer some compensation. Further, participants prefer progressive compensation to lump sum payments. Again, participants’ reaction to compensation is moderated by their belief in state intervention. Those who believe that state intervention is effective and appropriate react much more negatively to plans without compensation and show a stronger positive reaction to plans that offer progressive compensation.

Figure 2. Survey results on compensation preferences in Germany

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto

All in all, we and others find that political trust, or the belief that a government’s intervention will be effective, fair, free from corruption, legitimate, and credible, strongly moderates how the public reacts to various parts of climate policy.

How can policymakers increase trust?

If political trust is so important, can policymakers who want to boost public acceptance of climate action increase political trust? There are ways to render climate policy more trustworthy. Ideally, higher trustworthiness should translate into higher political trust by citizens, although the connection depends on how much citizens know about the government. Since political trust is a complex concept, how to render the government more trustworthy depends on where it falls short. Table 1 summarizes some potential sources of distrust and links them to examples of policy solutions. These solutions are not exhaustive but capture some of the mechanisms suggested in the academic and policy literature.

Table 1. Sources of Mistrust and Policy Solutions

| Source of Distrust | Examples of Policy Solutions |

|---|---|

| Perception of ineffective bureaucracy | Hire professional and impartial bureaucrats |

| Perceptions of high corruption | Open and transparent public procurement |

| Lack of fairness and political legitimacy | Inclusion of civil society in policymaking |

| Lack of credibility that policies will “stick” | Laws that are harder to overturn and inclusion of local communities |

An extensive literature has studied what makes political actors trustworthy in general (for an overview of the general literature on political trust, see Levi and Stoker 2000). This literature has highlighted the importance of competence and morality of officeholders and bureaucrats. While climate policymakers are unlikely to have the power to reform how the country’s bureaucracy as a whole is recruited and held to account, holding their own ministries to high moral and professional standards might render climate policymakers more trustworthy.

Further, Davidovic and Harring (2020), among others, show that political mistrust may derive from a perception of high corruption. While far-reaching anti-corruption measures fall outside the remit of climate policy, there are ways to lower the prevalence of corruption in climate-specific contexts. For example, when climate policy involves public procurement, corruption might be reduced by making the procurement process transparent and open to all companies. Further, international organisations, such as the United Nations, suggest that involving citizens in the procurement process can lower corruption.

Broadening participation can also improve other components of political trust. Bernauer and Gampfer (2013) demonstrate that individuals perceive climate policy as more legitimate when civil society is included in policymaking. In a recent book, Gazmararian and Tingley (2023) argue that delegating parts of climate policy to affected local communities can help persuade sceptical members of the public of a policy’s long-term credibility. The authors also suggest that governments should aim to pass climate laws that are more difficult to overturn in future election cycles. This is especially relevant in the US context, where a lot of climate policy has been historically conducted through unilateral presidential action, which is easily overturned.

Overall, there are ways to make climate policy more trustworthy, with the hope that this will increase political trust among citizens.

Conclusion

This research brief highlights the importance of political trust in creating acceptance of climate policies among the public. Since climate policy involves government intervention in some form, citizens are more likely to endorse it when they expect the government to choose and implement policy in a way that is fair, competent, free from corruption, legitimate, and credible in the long run. While it can be challenging to try and improve trust in the government as a whole, those who make climate policy can strive to become more trustworthy by, for example, increasing citizen and civil society participation in the policymaking and implementation process.

Based on:

- Mares, I., Scheve, K. & Toenshoff, C. (2024) Compensation, Beliefs in State Intervention, and Support for the Energy Transition. (Accepted, Comparative Political Studies, link to accepted version: German_Energytransition_Paper_2024.pdf (dropbox.com))

References:

- Bernauer, T., & Gampfer, R. (2013). Effects of civil society involvement on popular legitimacy of global environmental governance. Global Environmental Change, 23(2), 439-449.

- Davidovic, D., & Harring, N. (2020). Exploring the cross-national variation in public support for climate policies in Europe: The role of quality of government and trust. Energy Research & Social Science, 70, 101785.

- Edenhofer, J. & Genovese, F. (2024) PPRNet Brief When and Why Compensation Can Unlock The Green Energy Transition

- Fairbrother, M. (2017). Environmental attitudes and the politics of distrust. Sociology Compass, 11(5), e12482.

- Fairbrother, M. (2019). When will people pay to pollute? Environmental taxes, political trust and experimental evidence from Britain. British Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 661-682.

- Fairbrother, M., Sevä, I. J., & Kulin, J. (2019). Political trust and the relationship between climate change beliefs and support for fossil fuel taxes: Evidence from a survey of 23 European countries. Global Environmental Change, 59, 102003.

- Gazmararian, A. F., & Tingley, D. (2023). Uncertain futures: How to unlock the climate impasse. Cambridge University Press.

- Hammar, H., & Jagers, S. C. (2006). Can trust in politicians explain individuals’ support for climate policy? The case of CO2 tax. Climate Policy, 5(6), 613-625.

- Levi, M., & Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual review of political science, 3(1), 475-507.

Image: unsplash.com