The Liberals, the FDP has two seats in the Federal Council, but has been consistently losing voter shares and seats in parliament for a long time. After its recent losses, is the FDP still entitled to two seats in the national government at all? Daniel Bochsler has calculated all possible magic formulas and assesses the situation.

After the elections to the Council of States, the Alliance of the Centre party group is likely to be larger than that of the FDP. Will the FDP have to give up one of its two Federal Council seats?

Daniel Bochsler: I am curious about the second rounds of voting. However, there is no automatism in the magic formula. And it is even less clear what the magic formula is based on in the first place: the electoral strengths, or the composition of the Federal Assembly. In recent years, some parties have also interpreted new, creative elements into it. For example, that the cabinet composition at the federal level should be derived from that of cantonal governments, or that it should be calculated on the basis of imaginary blocks in parliament. The former may well make sense, but seems to be a pragmatic bending of the formula to justify seat claims. The latter would allow for flexible list combinations depending on the situation; they open the door to strategic games and deals.

If the FDP has to give up a seat, who should get it?

The FDP does not have to give up any seats at the moment. I don’t see any interest in this from the right-wing camp, and the Centre president says into every microphone held out to him that he will not vote out any incumbent federal councillors. This means that there is no majority for the removal of incumbent FDP mandate holders, performance record or not.

If there were an FDP vacancy, the Greens would probably be brought into play. By most calculations, they are more than half as strong as the FDP, and thus there is no question that the FDP can hardly justify a double representation as long as the Greens are not represented. Balthasar Glättli, president of the Green Party, likes to refer to the relevant calculation. He could reference the Sainte-Laguë electoral formula. It is not unknown in Switzerland; the canton of Basel-Stadt uses it to elect its cantonal parliament, and it underlies the double proportional representation that is used in a growing number of cantons. Glättli’s argument would be that it reflects the electoral votes or National Council seats as closely as possible.

In terms of voter shares, the SVP would be twice as big as the FDP, and thus closer to a third seat than the FDP is to the second. The SVP likes to insist on the arithmetical argument, but I have yet to hear the SVP call for a three-member representation. Either because it would look different depending on the composition of the Council of States and the underlying arithmetic, or because depending on the proportional representation formula used, i.e. if one were to calculate according to Sainte-Laguë rather than National Council proportional representation, the SVP would have to give arithmetic precedence to the Greens. But more likely because a third SVP seat would have no political chance anyway, and would probably be considered arrogant by the population. Moreover, the SVP does not want to bear too much government responsibility anyway, but as the only party in government with three representatives it should.

A Centre claim would only result according to the last of the ranking formula 2-2-2-1, with which the FDP has peddled in recent years. But I only see pseudo-arguments for this formula. If I understood it correctly, as it as never been clear, no party should be more represented in the Federal Council than the others, and fewer than four parties would be too few, more than four parties would be too many.

Of course, the 2-2-2-1 formula would become untenable if there were a party with an absolute parliamentary majority, because this party would of course have to provide at least four members of the Federal Council. Or if the fourth party were to fall into a low single-digit percentage. We will probably not see either of these cases in the next few decades, but these hypothetical examples show that a fixed ranking formula has nothing to do with supposed proportionality.

Of course, the Federal Council is not put together with a calculator, rather politically, and the Centre has an advantage in the party-political structure if it wants to dispute the second seat with the FDP, at best in a kind of alliance of convenience with the Green Liberal Party and an agreement that the seat should rotate. They probably have the median parliamentarian, i.e. neither to the right nor to the left of it can a majority be achieved without the Centre, and thus a lot of power.

Is there even a calculation formula for the composition of the Federal Council?

None of these calculations are recognised in any way. Unlike in Northern Ireland, for example, where there is a statutory proportional formula not only for the distribution of seats in the executive, but also for the distribution of ministries. Based on the number of seats in the regional parliament, an order is established according to which the parties can select ministries. This has the advantage that they do not even have to talk to each other to form the government. None of this holds true in Switzerland. In 1959, the SP, under the leadership of the then Conservative-Christian-Social People’s Party, the predecessor party of today’s Centre, won a second Federal Council seat, and various interpretations were then derived from this, but this is all ad hoc numerical magic. It’s more about political considerations. And often about the fact that there is little support for the current formula, but that there is no majority for a change.

Why is it not possible to derive a direct seat claim on the basis of voter shares?

That could be done, but that would be the system of a direct popular election by proportional representation, or an indirect mechanism formulated in such a way as to be equivalent to one. You don’t have to look far for an example of this, just look at Ticino.

In Switzerland, Federal Councillors are re-elected in the vast majority of cases. When would be the right time for a possible change in the party-political composition of the Federal Council?

If re-election is considered sacrosanct, the composition can only change in the event of death or voluntary resignation of a representative of the respective party. This also gives the party and its Federal Council members a strategic tool. As a result, members of the government who are tired of office may feel under pressure to stay in office longer than they would like, others may feel pressured to resign early. This could be remedied by deliberately voting them out of office, be it because of unsatisfactory performance, changing political alliances or electoral shifts. But majorities in the Federal Assembly are very seldom found for such things. Perhaps this has something to do with the election procedure, i.e. the single election. I dare not judge whether this unwritten principle of re-electing all members of government offers more advantages or disadvantages.

Daniel Bochsler is Associate Professor of Nationalism and Political Science at the Central European University (CEU) and Professor at the University of Belgrade. He completed his habilitation at the University of Zurich and is a private lecturer there. His research focuses on political institutions in divided societies, most recently in Central and Eastern Europe. He has published widely on Swiss politics, most recently with an outside perspective on Swiss democracy in the Oxford Handbook of Swiss Politics.

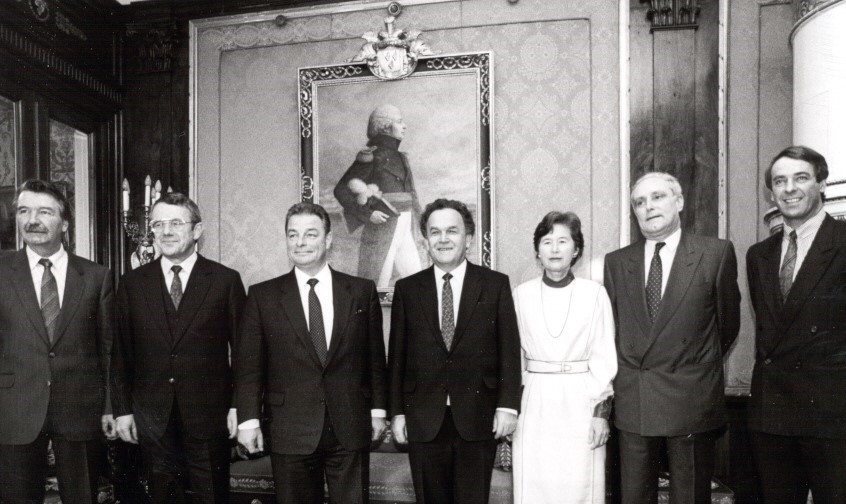

Photo: wikimedia commons