Since the mid-2010s, climate mobilisation has become a dominant force in the protest landscape of many democracies, featuring varying tactics ranging from school strikes and large-scale demonstrations to confrontational acts like street blockades and “art-attacks”. Public debate has been contentious, with strong concerns that confrontational tactics may provoke backlash and harm a progressive climate agenda. This policy brief first reviews the broader literature in protest research on the impact of climate mobilisation on public opinion and elite behaviour—key drivers of policy change. The core of this brief examines whether confrontational tactics indeed damage the movement’s goals. Findings from an original survey experiment in Germany (2022–2023) reveal that while confrontational protests are less favoured than mass demonstrations, support for climate policies remains stable regardless of the protest tactics.

Challenging two myths about the power of climate protest

Since the 1970s, environmental and climate mobilisation has seen cycles of activism and decline in established Western democracies (Borbáth and Hutter 2024). These movements have responded to nuclear energy policies, environmental disasters, disappointing climate summits, and the lack of progress toward transitioning from a fossil fuel-based economy. One common misconception is that mass mobilisation— such as the 2019 climate protests across Europe—fails to yield positive political or societal outcomes. Critics argue that despite movements like Fridays for Future, Western democracies are still not meeting CO2 reduction targets, fossil fuel dependency persists, and Green political parties are struggling to gain and maintain power. But is this assumption really justified? In 2021, the German Constitutional Court ruled that government policies must be recalibrated to protect the climate for future generations. This landmark ruling, along with other cases of policy shifts, raises the question of whether the massive climate mobilisations of 2019 might have played a role. While a direct causal link is difficult to establish, dismissing protest as ineffective risks overlooking its potential impact.

A second misconception revolves around the belief that confrontational climate protests, such as those led by Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil, the Last Generation, or The Earth Uprisings Collective, are counterproductive. Some claim these radical actions backfire, reducing public support for climate policies and hindering progress. In Germany, Last Generation has faced intense criticism, with politicians and media labelling them a criminal organisation and calling for stricter legal action. This narrative feeds into the belief that such protests not only fail to advance the climate agenda but actively harm it. However, this assumption deserves closer scrutiny. In our opinion, it is key to differentiate between the acceptance of specific protest forms and movements and the agreement on specific policy claims, i.e., the movements’ goals. Not all protest movements aim to be liked by the broader public. Instead, protest movements often aim to disrupt, especially movements with confrontational action repertoires. Should disapproval of a group’s actions, in these cases, lead to decreased support for specific policy claims? In this policy brief, we tackle both misconceptions or myths by, first, reviewing the literature on protest effects and, second, providing evidence that radical protest forms do not harm the movements cause.

Evidence 1: The political effects of climate protest

Protest mobilisation can impact society and politics in several ways. While the ultimate goal of protesters is often societal change or defending established rights, protest typically affects the policy-making process through various indirect channels rather than directly shaping legislation. The protest literature identifies four key channels through which protest influences politics: (1) affecting media coverage of the issues being protested; (2) shaping public opinion and voting behaviour; (3) influencing the behaviour of politicians and elected representatives; and (4) promoting or hindering the efforts of other protest groups and social movements. Social movement scholars have extensively studied these transmission channels. This section concentrates on two channels most directly connected to policy agendas: protest effects on public opinion and politicians’ behaviour.

Extensive research in political science and sociology has shown that protest, and in particular non-violent protest, can positively shape public opinion across different contexts. For example, studies have demonstrated that non-violent protests during the U.S. Civil Rights Movement led to more progressive public stances on racial issues and increased support for the Democratic Party (Wasow 2020). Non-violent protest can act as a vehicle for legitimating ideologies, exposing illegitimacy and instability, and providing an alternative vision for society (Thomas and Louis, 2014; Wouters 2019). In other words, when citizens are exposed to protest, they may adjust their norms and attitudes in line with the demands of the protesters.

Relatedly, local protests have been shown to signal constituent preferences to elected officials. As Gillion (2012) points out, protest resonates with politicians because it conveys information about the priorities of their constituents. Protests that are resource- intensive or face threats of repression are particularly strong signals of issue salience, especially for marginalised groups such as racial minorities (Gause 2022). However, protest alone is often insufficient; its impact on public opinion is crucial for influencing representatives’ behaviour in the policy- making process (Bernardi et al. 2021).

Turning specifically to climate mobilisation: Does climate protest matter for public opinion? Recent research confirms that climate protests do influence public opinion. For instance, Brehm and Gruhl (2024) show that after significant climate mobilisations, the public becomes more concerned with climate issues and pays more attention to climate protection. In Germany, evidence from Valentim (2023) indicates that constituencies experiencing Fridays for Future protests saw a 2.3 percentage point increase in vote share for the Green Party compared to areas without climate protests. This effect was even stronger in places with repeated mobilisations. In sum, climate protests have been shown to shift public opinion and increase electoral support for environmental parties.

Beyond influencing citizens, climate mobilisation can also impact political elites directly. Barrie et al. (2024), for instance, found that Fridays for Future protests in the UK influenced how politicians discussed climate issues in their online communications between 2017 and 2019. Similarly, Schürmann (2024) demonstrates that local protests by Fridays for Future shaped the climate agenda of MPs in the German Bundestag during the 2017-2021 legislative period. While climate protests influence politicians’ behaviour, the critical question remains: Can this translate into actual policy changes?

Similar to climate mobilisation today, empirical evidence from the U.S. (1960-1990) suggests that environmental protests can drive pro-environmental legislation, but two conditions are necessary: (1) the protest is mostly non-violent, and (2) the agenda- setting effect must succeed early in the legislative process to secure support for the movement’s cause later on (Olzak and Soule 2009). Therefore, it is important to recognise that protest is often not a sufficient condition to shift policy but can amplify its impact by raising awareness and informing politicians (Agnone 2007).

It is crucial to emphasize the sequential logic in the protest-policy link, particularly through public opinion and agenda-setting dynamics (Giugni 2007; Bernardi et al. 2020; Olzak and Soule 2009). Protest often indirectly influences politicians’ behaviour in the policy- making process, depending on its ability to first garner public support and shift the media agenda in its favour. These are challenging conditions for social movements to achieve and even more difficult for scholars to assess in terms of protest effects. Additionally, many social movements endure for years, decades, or even generations, with their impact unfolding not only sequentially but also over the long term. Nevertheless, as discussed earlier, there is strong evidence of direct effects from climate mobilisation on public opinion and voting patterns, which are critical precursors to influencing policy. Therefore, it would be far too premature to dismiss the power of protests and buy into the myth that they are ineffective.

Evidence 2: Radical climate protest may harm the movement, but not the cause

In the last decade, Western Europe has witnessed the rise of more radical climate groups like Just Stop Oil in the UK, the Last Generation in Germany, and The Earth Uprisings Collective in France. These groups are known for their confrontational protest tactics, including blocking streets by gluing themselves to the road, attacking art pieces, or disrupting major public and sports events. Note that we define non-violent confrontational actions as a radical protest form distinguishable from peaceful marches and other demonstrative actions, but clearly distinct from violent protests involving physical harm against persons as another radical protest form. Interestingly, these radical movements emerged after periods of mass demonstrations by the broader climate movement. Following the peak of climate protests led by Fridays for Future in 2019 (Borbáth and Hutter 2024), these radical groups formed across various Western European democracies.

The confrontational tactics used by these groups have sparked significant debate. Politicians, commentators, and journalists often claim that such confrontational actions damage the public image of the climate movement and hinder the broader cause of climate protection. Motivated by this widely held belief and aiming to contribute to the discussion on the effects of confrontational protest, we conducted a social scientific experiment to examine whether public support for climate protection policies actually suffers from confrontational protests. The experiment was implemented through a survey study among German adults in December 2022 and December 2023—a period during which the protest group Last Generation was particularly active. According to protest event analysis from the WZB ProtestMonitoring (Hutter et al. 2024), 19 per cent of the protests in 2022 and 2023 were led by Last Generation (339 out of 1,793 covered protest events). The survey was conducted using the online access panel provided by Respondi/Bilendi and included quotas for age groups, gender, and education to ensure a representative sample.

In the survey experiment, individuals were randomly assigned to a control group without treatment or to one of three different protest scenarios: (1) a peaceful demonstration, (2) an “art-attack” or (3) a street blockade where activists glued themselves to the road. The last two treatment scenarios are referring to radical or rather confrontational protest forms. For example, one of the treatment scenarios read as follows: “A few weeks ago, activists glued themselves to the city highway in Berlin. One member of the movement emphasised: “The Federal Government must fight climate change more decisively”. Following the experimental exposure, respondents reported their perceptions of the protest across three dimensions: support, sympathy, and legitimacy. Additionally, respondents were asked about their preferences towards climate protection. More specifically, we asked: “To what extent do you support the demands for the federal government to more decisively combat climate change?” The random assignment of the protest scenarios allows us to infer causal claims from the results, since socio- demographic and political characteristics of the respondents are similarly randomly assigned across treatments.

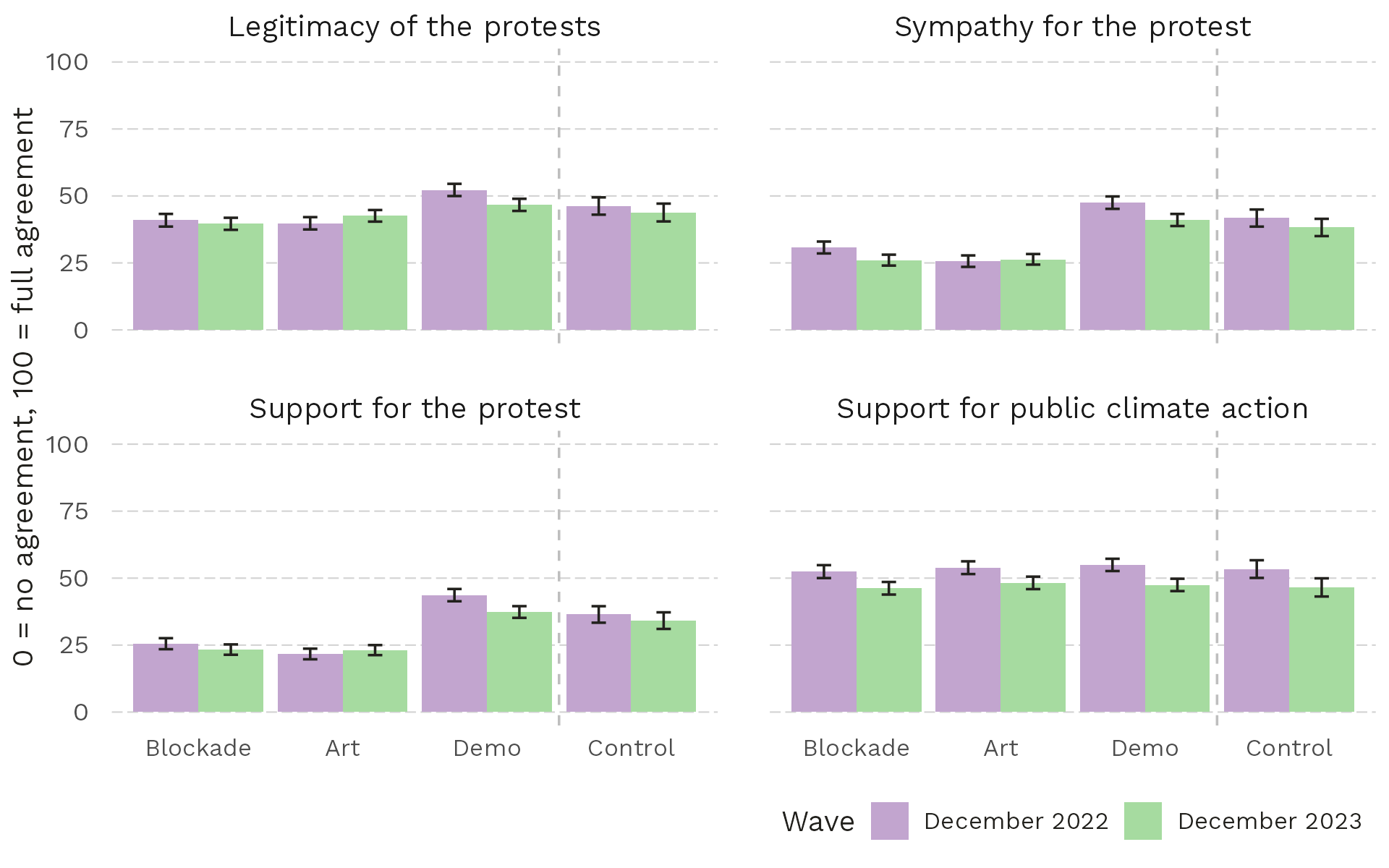

Figure 1. The effects of protest forms on support for the protest and climate protection policies

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto · Data: ??

Note: The mean agreement across the three perception dimensions of the protest and support for climate action is represented by the bars; error bars depict 0.95 confidence intervals of the mean. Absolute differences are causally inferable in statistical terms due to the randomised assignment of the treatment groups. Sample size: wave of December 2022 – N = 2,824; wave of December 2023 – N = 2,936. Source: Saldivia Gonzatti, Hunger and Hutter 2023.

Our findings, displayed in Figure 1, reveal three important lessons. First, confrontational protest forms such as “art-attacks” and street blockades are penalised across all three dimensions of support when compared to peaceful demonstrations. These radical actions are viewed as less legitimate and garner lower levels of sympathy and active support. Second, peaceful demonstrations generate positive effects across all three perception dimensions of the protest, even exceeding the approval rates of the control group that was not exposed to any form of protest. This confirms the negative impact of confrontational protest on movement support when compared to peaceful demonstrations. Interestingly, peaceful protests enhance the image of the climate movement overall, regardless of the presence of more radical actions. Third, we address the potential effects of different protest forms on support for public climate action to determine whether the negative impacts of radical mobilisation on support for the movement extend to support for progressive policy agendas. Our findings show no evidence of this. The lower panel of Figure 1 illustrates that the various protest scenarios do not significantly influence policy preferences among the German public in our survey study. In the second wave of the survey, conducted in December 2023, we also analysed preferences for specific and costly policies, such as heating system replacement and renewable energy adoption. Again, we found no variation in support levels based on the type of protest. In summary, despite concerns raised in political commentary, radical protest forms do not appear to negatively affect public support for climate protection policies, at least in the short term.

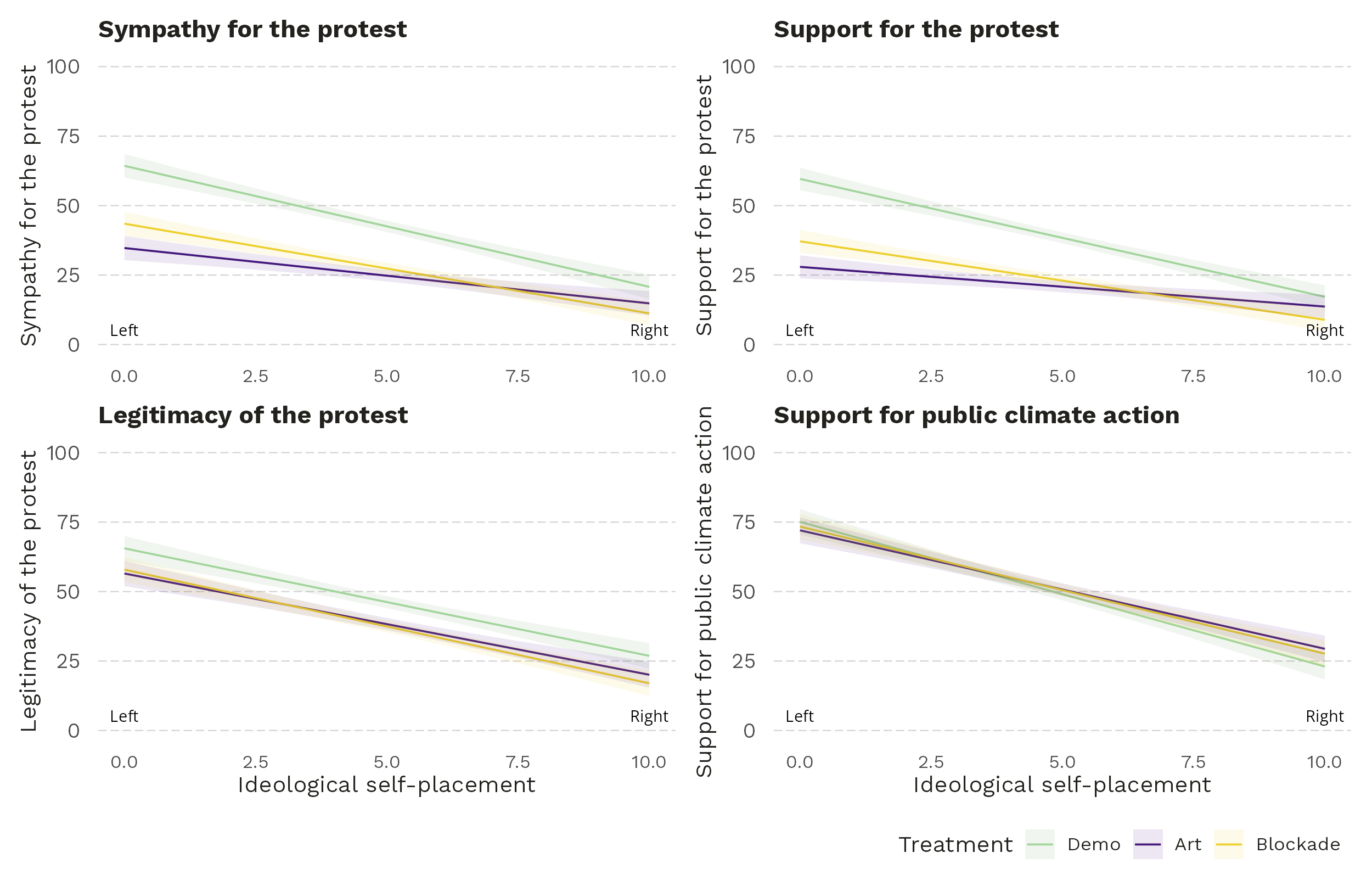

In Figure 2, we analyse the protest effects across the respondents’ diverse left-right self- placements. Regarding the three dimensions of movement support, it is evident that the negative impact of confrontational protest forms is primarily driven by respondents on the political left and the political centre. In contrast, while they report the lowest approval scores overall in absolute terms, the different protest forms do not affect the approval of the movement among right-wing individuals. In other words, confrontational protests, as opposed to peaceful demonstrations, damage the movement’s image among potentially progressive individuals but have no significant effect on the already low approval from right-wing individuals. Additionally, consistent with the above reported findings, confrontational protest forms do not reduce support for climate protection policies across the ideological spectrum.

In sum, two key insights emerge regarding the effects on different ideological groups. First, right-wing individuals show the strongest opposition to the climate movement and the least support for climate policies, regardless of the protest form. Second, while individuals on the left express disapproval of confrontational protests compared to peaceful demonstrations, this does not alter their preferences for climate protection.

Figure 2. Ideological heterogeneous effects of protest forms on support for the protest and climate protection policies

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto · Data: ?

Note: The predicted values represented in the interaction lines depict the different agreement levels of the three perception dimensions of the protest and support for climate action across different levels of individual’s ideological self-placement (left-right); 0.95 confidence intervals. Control treatment group excluded for visualisation reasons. Predicted values based on regressions with OLS specification controlling for survey wave and accounting for individuals’ gender, age, and education.

Our survey experiment contributes to the broader discussion on the effects of radical protest tactics on movement and policy support. Similar findings have emerged in other contexts. For example, Budgen (2020) finds no “backfire” effects in his survey experiment on climate protests among US respondents. In a different context of progressive politics, Enos et al. (2019) report that violent protests had a positive effect on local support for liberal racial policies following the 1992 Los Angeles Riots. More recently, Olzak (2024) studied the impact of exposure to violent Black Lives Matter protests in the US, with nuanced outcomes: while violent protests reduced the intention to vote for a Republican presidential candidate, they had no effect on voting for a Democratic candidate. Yet, her panel study also reveals that violent protests decrease the endorsement of liberal solutions to urban unrest and may thus “undermine the convergence between an individual’s attitudes toward a movement and its goal” (p. 302).

Overall, it is important to highlight that our study offers novel evidence on the distinct effects of confrontational protest forms (which represent a mild version of radical actions compared to violent ones) on support for both the movement and its cause in a growing and dynamic research field. Our findings specifically capture short-term effects and do not account for potential cumulative impacts over time. Nevertheless, the empirical evidence challenges widespread misconceptions in public debates, particularly the assumption that confrontational climate mobilisation invariably harms the movement’s goals.

Discussion and implications

The rise of climate mobilisation in established democracies over the past decades has sparked controversial debates about its strategies and effectiveness. In this policy brief, we summarised empirical evidence on its impact on public opinion and the behaviour of political elites. The climate movement has demonstrated substantial potential to influence the public and shift voter preferences toward more climate-friendly policies. Simultaneously, climate protests have proven capable of shaping the issue agenda in parliament and influencing how MPs allocate their attention during parliamentary speeches. Raising public and political awareness for climate protection is a crucial step for climate mobilisation to ultimately affect policy-making processes, as the direct link between protest and policy change is often weak. This suggests that climate protests can benefit from a positive public image and strategic alliances with political parties and established actors to push a progressive agenda from the early stages of policy development. Our findings challenge the myth that climate protests cannot have a positive impact on politics and policy.

However, the question of whether the negative image associated with confrontational climate actions can harm the policy goals of the entire movement remains contentious. Our experimental study shows that confrontational protest forms, such as street blockades, do indeed leave a negative impression on the public. Individuals tend to express less support and acceptance for such forms compared to mass demonstrations. Nevertheless, we provide evidence that people’s climate policy preferences remain stable even when exposed to these unconventional protests, despite their disapproval of the methods. Importantly, it is primarily progressive individuals who exhibit this discrepancy. Conservative and right-wing individuals, on the other hand, maintain a uniformly negative view of any type of climate mobilisation and show very low support for climate protection overall. This implies that while unconventional protest forms may be viewed unfavourably, they do not necessarily lead to losses for the climate cause.

This finding holds significant implications for progressive movements and political projects, suggesting that potential alliances with more radical protest groups can be viable even if their strategies differ. Additionally, the evidence suggests the potential for positive “radical flank effects” from confrontational protests. This means that more moderate protest actors and forms, such as peaceful demonstrations, may actually gain legitimacy and increased support when confrontational protests occur alongside them. However, caution is warranted, as climate issues have become increasingly polarizing in many advanced democracies. Thus, the effect of protest, whether supporting or opposing ambitious climate policies, may largely reinforce pre-existing beliefs, making it more challenging to sway public opinion and influence elite behaviour.

Based on:

- Saldivia Gonzatti, Daniel, Hunger, Sophia & Hutter, Swen (2023). Environmental Protest Effects on Public Opinion: Experimental Evidence from Germany (Analysebericht). https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/5mb3u

- Hutter, Swen, Hunger, Sophia, Saldivia Gonzatti, Daniel & Schürmann, Lennart (2024). WZB ProtestMonitoring 1950-2023. WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

References:

- Agnone, J. (2007). Amplifying public opinion: The policy impact of the US environmental movement. Social Forces, 85(4), 1593-1620.

- Barrie, C., Fleming, T. G., & Rowan, S. S. (2024). Does Protest Influence Political Speech? Evidence from UK Climate Protest, 2017–2019. British Journal of Political Science, 54(2), 456-473.

- Bernardi, L., Bischof, D., & Wouters, R. (2021). The public, the protester, and the bill: do legislative agendas respond to public opinion signals? Journal of European Public Policy, 28(2), 289-310.

- Borbáth, E., & Hutter, S. (2024). Environmental protests in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 1-26.

- Brehm, J., & Gruhl, H. (2024). Increase in concerns about climate change following climate strikes and civil disobedience in Germany. Nature Communications, 15(1), 2916.

- Bugden, D. (2020). Does climate protest work? Partisanship, protest, and sentiment pools. Socius, 6, 2378023120925949.

- Enos, R. D., Kaufman, A. R., & Sands, M. L. (2019). Can violent protest change local policy support? Evidence from the aftermath of the 1992 Los Angeles riot. American Political Science Review, 113(4), 1012-1028.

- Gause, L. (2022). Costly protest and minority representation in the United States. PS: Political Science & Politics, 55(2), 279-281.

- Giugni, M. (2007). Useless protest? A time-series analysis of the policy outcomes of ecology, antinuclear, and peace movements in the United States, 1977-1995. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 12(1), 53-77.

- Olzak, S., & Soule, S. A. (2009). Cross-cutting influences of environmental protest and legislation. Social forces, 88(1), 201-225.

- Olzak, S. (2024). The Consequences of Violent and Non-Violent Black Lives Matter Protest For Movement Support. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 29(3), 287-307.

- Schürmann, L. (2024). The impact of local protests on political elite communication: evidence from Fridays for Future in Germany. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 34(3), 510-530.

- Thomas, E. And Louis, W. (2014). When will collective action be effective? Violent and non-violent protests differentially influence perceptions of legitimacy and efficacy among sympathizers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40(2):263–276.

- Valentim, A. (2023). Repeated Exposure and Protest Outcomes: How Fridays for Future Protests Influenced Voters. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/m6dpg

- Wasow, O. (2020). Agenda seeding: How 1960s black protests moved elites, public opinion and voting. American Political Science Review, 114(3), 638-659.

- Wouters, R. (2019). The persuasive power of protest. How protest wins public support. Social Forces, 98(1), 403-426.

Image: unsplash.com